Update on Anglo-Irish Negotiations

23 July 1921

The Times, 23 July 1921

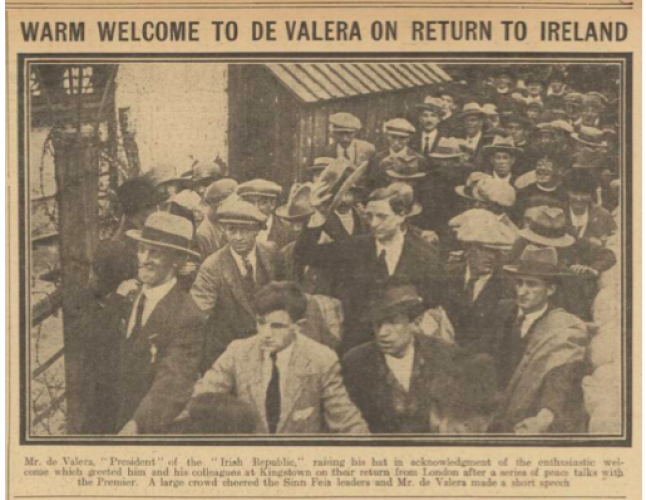

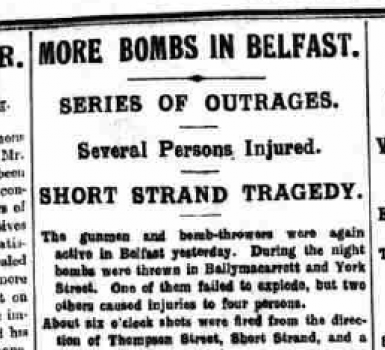

In July 1921, British and Irish forces agreed a truce to end the Irish War of Independence. An Irish delegation, including Éamon de Valera, then travelled from Dublin to London to meet with British Prime Minister David Lloyd George. Though the meetings ended without a formal agreement, both parties agreed to a continuation of the truce and a commitment to continue talks. These meetings laid the foundation for the later negotiations which led to the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in December.

Irish Peace Plan

(By Our Parliamentary Correspondent.)

Mr. de Valera has expressed the wish that the terms of the Cabinet’s offer for the settlement of Ireland should not be published before he has communicated them to his principal supporters in Ireland. Mr. Lloyd George has agreed, and an arrangement is to be made for simultaneous publication in Ireland and here. It is expected that Dail Eireann will be summoned without delay.

The document which Mr. de Valera has taken back with him is understood to give in broad but exact outlines the new arrangements which the Cabinet has approved for the appeasement and reconciliation of Ireland. It avoids details and is concerned only with the large lines of future relations between North and South Ireland and between Ireland and Great Britain.

The proposals are based on Dominion self-government. They are made to the South. They are also made to the North. If the South accepts it will be open to the North independently to reject them. Then there would be an unhappy perpetuation of what Sinn Fein has stigmatized as partition. It is part of the Cabinet’s scheme that Ulster must not and cannot be coerced and that Sinn Fein should recognize the justice of applying to the North the principle of self-determination in local affairs which is the basis of its claim for Ireland as a whole. But while, according to the Cabinet’s plan, the North is to retain in full measures the safeguards provided by the Better Government of Ireland Act, there will be very strong inducements for North and South to co-operate in establishing and maintaining a central governing authority for the whole of Ireland to deal with questions of common interest.

North and South

The Dominion powers proposed to be conferred are very wide. It will probably be found that with the single exception that certain military safeguards are reserved for the Imperial Parliament, the full range of Dominion authority is to be offered alike to the Parliament of the South and to the Parliament of the North. If the North were to decline the new powers the Southern Parliament would be able to exercise them in the 26 counties under its jurisdiction…

The scheme represents the full scope of what the Cabinet has to offer. It is an outline. The detail has still to be sketched in. But the outline marks the limits to which the Cabinet is prepared to go, however important some of the details may be. The scheme depends for its acceptance on the enlarged powers of self-government it offers to the Irish Parliaments, on the maintenance of guarantees to Ulster, and on the encouragement and powerful inducement it gives to the co-operation for purposes of all-Ireland government of the governing bodies in the North and South.

It is a hopeful sign that Mr. de Valera and his colleagues left London in a cheerful state of mind. “Though the immediate future is uncertain,” Mr. de Valera said, “we have perfect confidence in the ultimate success of our cause.” It is also a good omen that Mr. de Valera desires himself to submit the Cabinet’s plan to Dail Eireann. His motive—and this governs his request for the postponement of publication—is believed to be a desire to prevent the spread of unofficial and possibly misconceived interpretations. One definite fact is that the demand an Irish Republic is made no longer.

There is a possibility that General Smuts may visit Ireland next week.