Experiences of an Officer’s Wife in Ireland Published

02 July 1921

The Illustrated London News, 2 July 1921

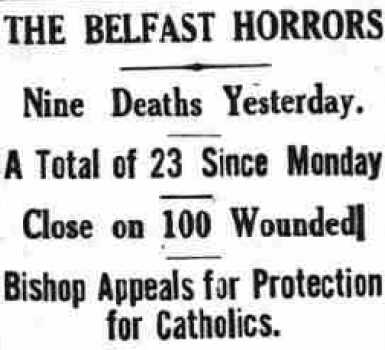

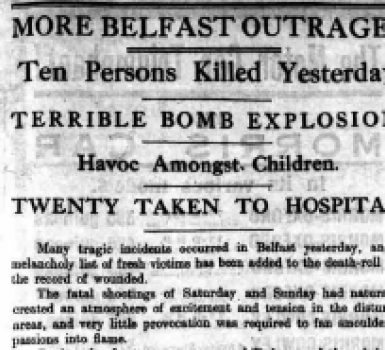

In July 1921, The Illustrated London News reported on the publication of Experiences of an Officer’s Wife in Ireland, a memoir written by Caroline Woodcock, wife of Major Wilfred Woodcock. The book offers the perspective of a British Officer’s Wife living Dublin during the War of Independence, including a detailed account of Bloody Sunday (21 November 1920).

An Officer’s Wife in Ireland

Of all sufferers from the Irish Terror none deserves greater sympathy than the womenfolk of soldiers compelled by military duty, usually against their will, to be concerned in the feuds of a distracted nation. Their point of view is expressed, with unflinching candour and mordant wit, in a little book of reminiscences called “Experiences of an Officer’s Wife in Ireland” (Blackwood), published anonymously.

The author accompanied her husband to Dublin when he was ordered thither last year. “He was a regimental officer, and had nothing whatever to do with politics, secret service, or police; and we were always told that the Regular soldiers were popular, and that the people fully realised—as was, and is now, an undoubted fact—that the British officer stood between them and ruin. For had it not been for the regimental officers, and the discipline they enforced, Dublin would have been burned long ago.” Nevertheless, he was one of those assailed on that ghastly “Red Sunday” (Nov. 21, 1920) when fourteen British officers were murdered in cold blood, some in the presence of their wives. Of six officers living in the same house, the writer’s husband and another escaped with wounds, but the rest were killed. “Never to my dying day,” she writes, “shall I forget the scene.”

Accursed Country

It is hardly surprising to find her later describing Ireland as “that accursed country,” of which “every stick and stone will be for ever hateful to me.” She had gone there with very different feeling, “prepared to love the country and the people,” and “genuinely interested In the Sinn Feiners,” having “a good deal of sympathy with them.” She does not pretend to go into history of politics; she “has no views” on the Irish question — “the situation is too complex for anyone of ordinary intelligence” — but she throws a strong light on the externals of life in Dublin as she saw it, and she pays a high tribute to the conduct of the troops. While the actual murder scene is the climax, there are many others, less tragic though equally illuminating, on domestic and social details, types of character, journeys, Dublin Castle, and the court-martial at which she was required to give evidence. Whatever settlement may ultimately be made in Ireland, this little book adds an indelible page to Irish history.