De Valera Agrees to Negotiations

30 September 1921

1 October 1921, Londonderry Sentinel

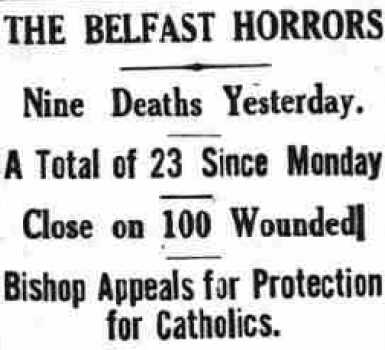

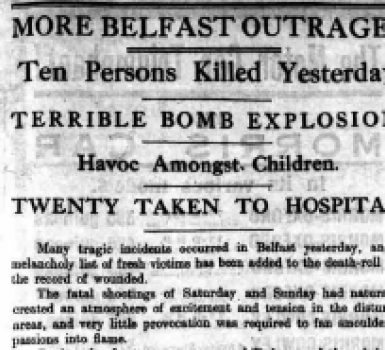

While the ceasefire between British and Irish forces began in July 1921, it was not until the end of September that both parties agreed to undertake in-person negotiations to develop a peace treaty. The main reason for the delay was wrestling over the basic principles under which the talks would occur: de Valera wished Ireland to be entirely separated from Britain, while the British insisted that loyalty to the King and some form of association must remain. Both sides modified their positions until eventually the British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, sent de Valera an invitation to a conference that he felt he could accept. On 30 September 1921 Éamon de Valera wired acceptance of the invitation to Westminster, and in 11 days one of the most fateful negotiations on the future of the island of Ireland would begin. Many unionists were unhappy with the concessions Lloyd George had made to get the republican representatives to the table. This editorial from the unionist Londonderry Sentinel scathingly criticised the terms under which the negotiations were due to take place.

'FRESH' INVITATIONS

It is on record that after despatching on Thursday his “fresh invitation” to a Conference Mr. Lloyd-George went fishing. One is reminded of the spendthrift Irish landlord who, upon signing a bill on which to raise money to pay some of his debts, exclaimed, “Thank heaven, that’s off my mind.” The Imperial Prime Minister having, with the assistance of the concentrated wisdom of all his Cabinet colleagues, arrived at a formula which his political instinct told him the “President” would accept, felt sufficiently light-hearted to occupy the day seeing whether another 8lb. salmon should not fall to his adroitness in angling. Sufficient for the day is the letter thereof. Enough for him that, regardless of the future of his action, he has made a sufficient surrender to warrant Mr. De Valera’s acceptance.

UNDUE OPTIMISM?

The expected has happened. The “President” has promptly wired acceptance. Dublin is delighted to find that its optimism all along is proved to have been justified. But, while Belfast is not surprised, it is by no means optimistic regarding the outcome of the Conference, when it takes place. Why should there be optimism anywhere? The fact of Mr. Lloyd-George inferentially cancelling all the conditions, and even dropping out all reference to the need for a preliminary recognition of the King’s sovereignty, makes no difference: Mr. De Valera will go into the Conference as the “President of the Irish Republic.” Has he not informed the Premier that “we can only recognise ourselves for what we are”? How long will it be, in the course of the negotiations, before the British Ministers will discover that Mr. De Valera recognises himself for something which his Majesty’s Government cannot possible assent to? For how long can the discussion go on before Mr. De Valera will stand forth openly and avowedly as a Republican President, able to point to his force of drilled men – drilled largely during the truce – his “courts,” civil and criminal; his “Parliament” of men who have taken an oath to “support and defend the Irish Republic,” and his scores of thousands of supporters at the ballot-boxes? What will happen then?

A WAITING GAME

Can the exploration of every avenue go further, having regard to the suggestion, even in the last conciliatory British letter, that there is something “fundamental to the existence of the British Empire” which the Government cannot give up? It may be argued by what we may call the Conference-at-any-price party represented by the London “Times” and the Radical English Press that in some way or another Mr. De Valera, or – if the “President’s” dignity will be compromised by his going personally to confer with a mere Minister – whoever takes his place in Downing street will manage to keep such awkward questions as the supremacy of the Crown out of the discussions. But how can the principles on which the twenty-six counties are to be governed be laid down without the form of government being specified – unless the parties to the Conference agree with each other to play a game of make-believe with the object of humbugging the British public? However, Mr. Lloyd-George has got his Conference. The country will “wait and see” what comes of the unprecedented experiment in exploration, the outcome of the exploits of the gunmen on the one hand and the nervousness of the King’s advisers on the other.