The Northern Ireland Economy Between the Wars

26 July 2021

.png)

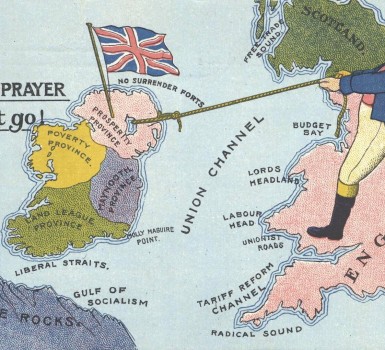

In 1920, while Ireland remained a predominantly agricultural economy, the north-east was the only part of the island to have experienced an industrial revolution. The economic core of the new state was its manufacturing sector concentrated in linen, engineering and shipbuilding. The First World War had brought prosperity to the whole of Ireland and the North’s main industries experienced boom conditions which continued into the immediate post-war period.

However, within a year the economic situation had changed dramatically. Throughout the interwar period Northern Ireland economy suffered from high rates of unemployment: 19 percent on average between 1923 and 1930 and 27 per cent between 1931 and 1939.

Decline of Key Industries

These high rates stemmed from the problems experienced by Northern Ireland’s three staple industries: shipbuilding, linen and agriculture which during the period accounted for between 40 and 50 percent of the working population. All three were adversely affected by international economic developments which industrialists, farmers and governments were powerless to control.

Similar problems occurred in other parts of the UK where there was a high dependence on a few industries like coal, steel and shipbuilding. There was also a failure to attract the new industries orientated to domestic consumption which developed in the midlands and south-east of England in the period. The only success was the foundation of the Short and Harland aircraft factory at Sydenham in east Belfast in 1937.

The new devolved government had only limited powers to deal with the economic and social problems of the region. The Government of Ireland Act reserved the major forms of taxation: income tax and customs and excise to Westminster leaving the Northern Ireland state with relatively minor taxation powers for vehicles, death duties and dog licenses.

The revenue due from the reserved taxes paid by Northern Ireland citizens was calculated by a Joint Exchequer Board with representation from the North’s Ministry of Finance and the Treasury. Once the cost of all Northern Ireland’s services had been met, there was to be an Imperial Contribution to help cover the costs of the army and navy and other imperial responsibilities. This was to be a first charge on the North’s budget.

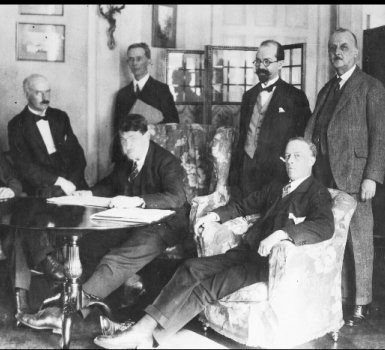

Depression

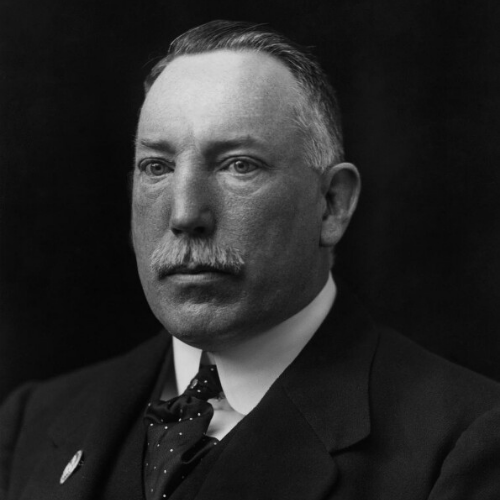

These provisions were made inoperable by the severe economic problems of the 1920s and 1930s. Depressed economic conditions brought down tax revenues but Sir James Craig’s government insisted that the citizens of Northern Ireland should not accept lower standards of social benefits then their fellow British citizens. A policy of ‘step by step’ ensured that in certain areas of social expenditure: unemployment and sickness benefit and old age and widows’ pensions the benefits were at the same level as across the Irish Sea.

This was only possible because the Treasury reluctantly accepted the recommendation of an arbitration committee, chaired by Lord Colwyn, that the Imperial Contribution would cease to be a first charge on revenue but a residual item with the result that it practically disappeared in the early 1930s.

Health and Housing

However, in other areas of social policy like housing and health the record of provincial and local government was poor. This was in large part because the Treasury did not accept until after 1945 that it should subsidise the devolved government to establish parity of social provision in all spheres. One authority pointed out that the pre-1939 record of local authorities and central government in Northern Ireland was dismal in contrast with England and Wales. This reflected the relative poverty of the region but also the conservative philosophy of many local councillors who opposed increasing rates on property and business to finance house building for the working class.

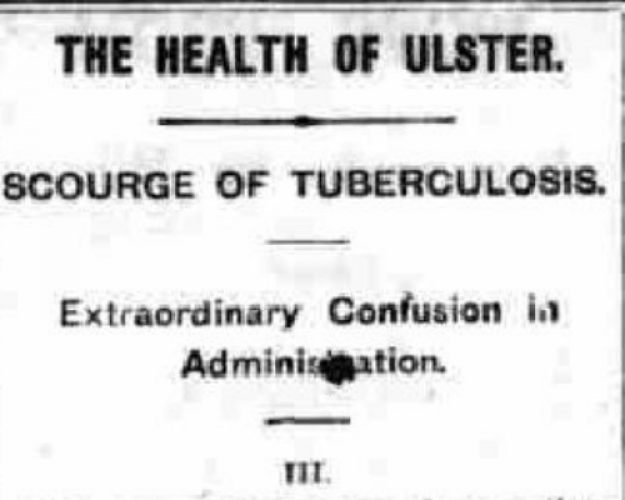

Although a Ministry of Health was created in Britain after the First World War, health services in Northern Ireland remained largely with the Boards of Guardians and local authorities. Tuberculosis was rife but in 1923 only three of eight counties and county boroughs provided sanatoria with a total of 375 beds. No more public sanatoria were built between the wars.

In 1922-24 Northern Ireland had the highest TB death rate in UK and Ireland by the end of the 1930s although death rates had fallen considerably, Northern Ireland still suffered from the highest rate in the UK. Belfast also was judged by an independent investigation in 1941 to have a medical service that fell far short of what might be expected in a city of its size. People in Northern Ireland had worse mortality rates than anywhere else in the UK. Only Scotland had worse maternal and infant mortality rates.

The Welfare of the People?

On the 23 June 1921 Sir James Craig declared , “We have nothing in our view except the welfare of the people.’ Taking power in a region significantly poorer than much of the rest of the UK and which then endured two decades of difficult economic conditions , the government could claim to have maintained key social entitlements to a substantial sector of the population. It also had some success in improving methods and productivity in agriculture but was largely unsuccessful in developing or attracting new industries to compensate for the stagnation or decline of its traditional manufacturing sector.