Focus On... Religion

03 November 2021

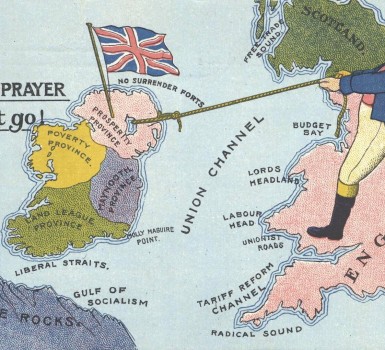

Religion, especially when placed in the context of Irish partition and the creation of Northern Ireland, has often been characterised simply as a marker for other political, cultural, and ethno-national identifiers.

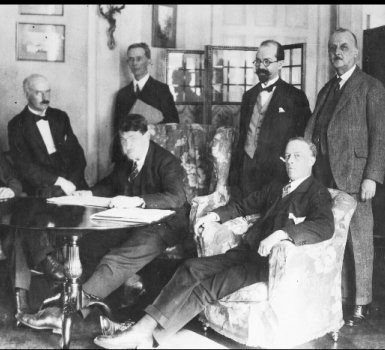

The use of religion as a synonym for Ireland’s broader divisions was perhaps best encapsulated in a 1934 speech by the Northern Ireland Prime Minister James Craig, during which he famously described Northern Ireland as a ‘Protestant state’ and the then-Irish Free State as a ‘Catholic state’. This same distinction was also evident within Northern Ireland after 1921, where the communal tensions between the new state’s Protestant and Catholic communities were viewed as synonymous with the political tensions between Ulster unionism and Irish nationalism.

Indeed, politics and religion were closely intertwined even within the churches themselves. The Catholic Archbishop of Armagh Cardinal Michael Logue declined Craig’s invitation to attend the state opening of the Northern Ireland parliament, and the Catholic Church – initially at least – also boycotted the new state at a local level, especially concerning education.

However, despite the close links between religious and national identities in Ireland, the development of religion in its own right must not be ignored. By the early twentieth century, Ireland was one of the most pious places in western Europe, and the extremely high levels of church attendance and popular devotion in Belfast set it apart from most other industrialised cities where organised religion had begun to lose its grip on the urban working class. This popular piety owed much to the effects of the ultramontane ‘devotional revolution’ within Catholicism and the growth of Protestant evangelicalism in the nineteenth century. While revitalising popular religion in Ireland, these developments also fostered an atmosphere of sectarian exclusiveness, particularly evident in the Catholic hostility to mixed marriages, and religious controversy stoked by anti-Catholic preachers.

The tumultuous establishment of the Northern Ireland state also coincided with major religious developments. In 1921 the evangelist preacher William Patteson Nicholson began a series of missions which swept Protestant Ulster for the much of the following two years, and were credited by his supporters as stopping the outbreak of civil war in Northern Ireland. Though Nicholson stayed out of politics (as you can see in his speech below), he became an increasingly divisive figure within Ulster Presbyterianism. He was associated with the growing fundamentalist movement against theological modernism in the Presbyterian Church in Ireland which eventually culminated in the unsuccessful heresy trial of J. E. Davey in 1927, and was cited by Ian Paisley as an inspiration for his own preaching career.

Below you can find a range of viewpoints from across the denominational spectrum on the development of religion – and its relationship with the broader political climate, or otherwise – at the time of partition.

Cardinal Logue’s speech at the Catholic Truth Society

Irish Examiner, 22 October 1920

‘I hope that the troubles and the difficulties that we have at present will vanish, and that the time is not far distant when our country will have peace, tranquillity and prosperity. There is one thing she is sure to have – she will never turn her back on the old Faith of St Patrick (applause).

We have passed through times as calamitous as the present time, and they were worse in one way, inasmuch as they were directed against our Faith. We have passed through these times, and the Faith is as strong in Ireland now as if we never had either persecution or contradiction, or any of the temporal or spiritual miseries which have been brought upon us by our neighbours.

I hope, therefore, that with God’s help, if we keep quiet and keep with God’s Law, and say our prayers, and say them well – there is no use in saying prayers if we are careless about them – I hope that the time is not far distant when Ireland will be what she has been in the past – the Island of Saints and Scholars; the first flower of the earth and the first gem of the sea.’

‘The State of the Country’ report, General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in Ireland

Skibbereen Eagle, 18 June 1921

‘The fact that two parliaments are set up need not separate the people of Ireland. It simply means that two communities which are different in many respects will each be able to carry out its own ideals with the least possible friction. We know that while most of the Presbyterians are under the Northern Parliament, a large and important section of our Church will owe allegiance to the Southern Legislature. But the unity of our Church will not be impaired by being under separate Legislatures, rather the bonds of fellowship and harmony will be closer than ever.

One of the fundamental principles of the reformed faith is the right of conscience, the right of every man to think for himself according to the light which God has given him. True to that principle, our Presbyterian people wish to live at peace with their Roman Catholic fellow-countrymen in the new order of things in Ireland.’

‘Hopes of unity, peace, and concord’. Speech by Maurice Day, Church of Ireland Bishop of Clogher

Londonderry Sentinel, 15 October 1921

‘I do not wish in this or any other synodical address to enter into politics, and I shall be as brief as possible in referring to this Act, which is entitled, perhaps in a spirit of optimism which as yet has not been realised, “An Act to provide for the better government of Ireland”. A few features of this Act, especially as it affects us in this diocese, I must touch upon.

“Partition” seems to be largely at the foundations of its provisions, the partition first of all of the United Kingdom… as a lifelong Unionist and as one who signed the Ulster Covenant, I must continue my protest against the dissolution of the Union ... a protest which has been solemnly and emphatically been entered by the Church of Ireland, as well as in our own Diocesan Synod. But in this Act we have another stage of partition – the division of Ireland herself into two portions. I shall only remark… that what to me is the one gratifying fact is that in the Home Rule Act the door is not closed against a possible reunion of Ireland under one Legislature and Parliament.

A third partition has resulted in Ireland as a consequence of the Home Rule Act, which we who reside in this country of Monaghan deeply regret, if, indeed, we do not strongly resent, and this is the partition of Ulster itself. And this leads to one other stage of partition in Ireland and this is that our very diocese of Clogher is to be politically sub-divided. However, this stage of sub-division need not trouble us, as we are engaged in the higher responsibilities of the work of the Church of God. I feel confident that no political division will in the slightest interfere with the cordial and united co-operation, as heretofore, of all the members of the Church of Ireland clergy and laity, working together for God and Christ in one diocese and under one Bishop.’

W. P. Nicholson’s mission campaign

Newtownards Chronicle, 5 November 1921

‘Ye must be born again. There is no substitute for this … You may be a minister, or an elder, or a deacon, or a Sunday School teacher, or an evangelist, or a missionary; but ye must be born again. If you are rich, you must be born again; if you are poor, you must be born again; if you are learned, you must be born again; if you are a Presbyterian, or a Methodist, or an Episcopalian, you must be born again; if you are a Sinn Feiner or an Orangeman, you must be born again. There are not 50 ways to heaven; there is only one. You must be born again.’

Dr Ryan Mallon, Queen's University Belfast