Ulster Unionism and the constitutional routes not taken

07 January 2022

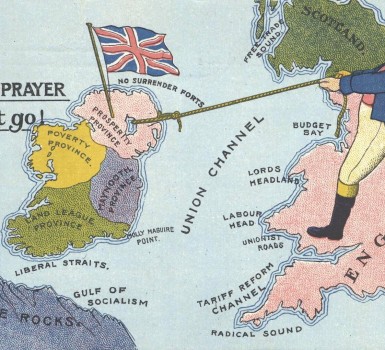

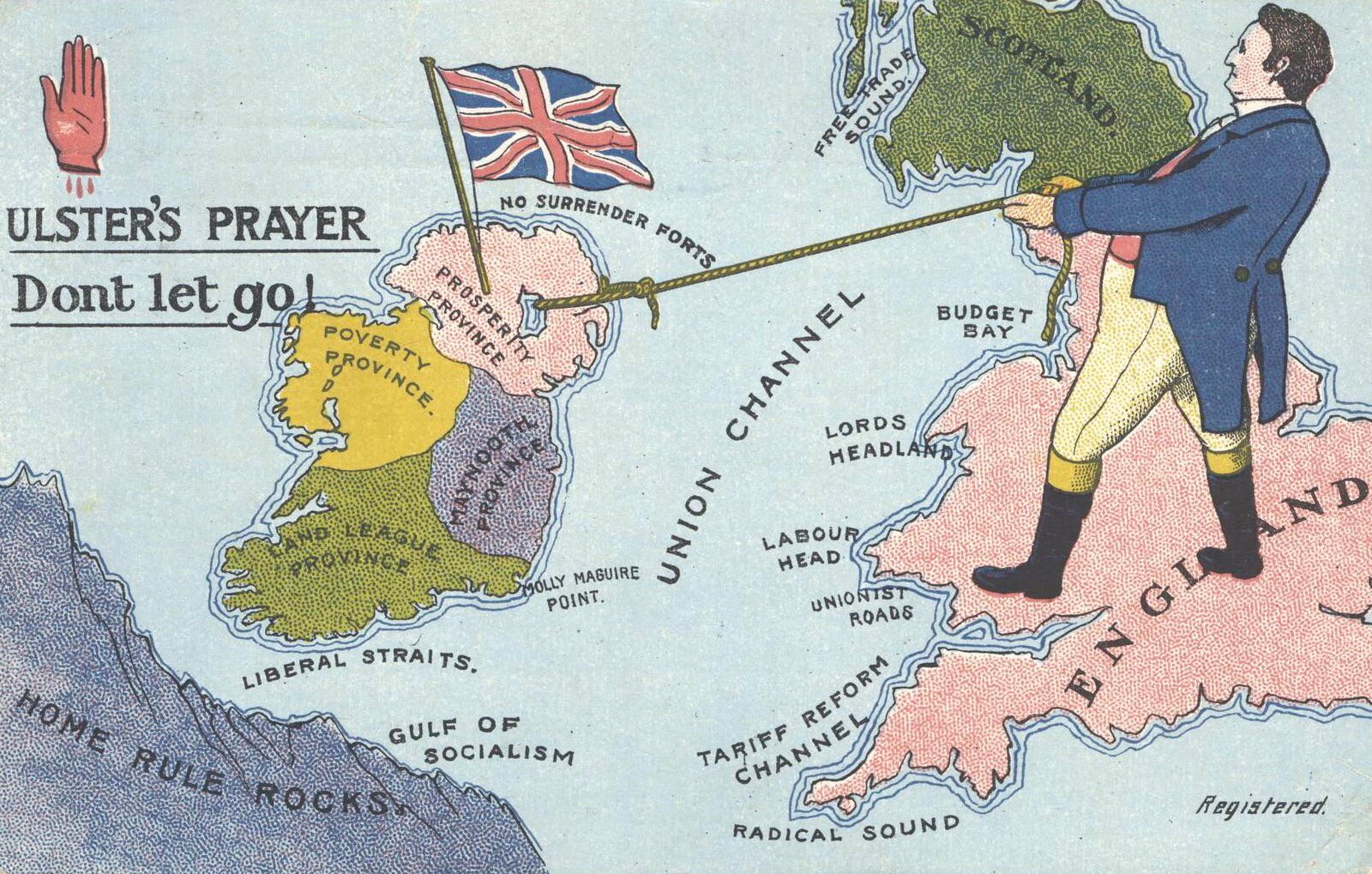

Accepted on a principle of ‘what we have we hold’, Northern Ireland’s first Prime Minister James Craig saw the value in partition and devolution as symbols of Protestant unionist strength. Northern Ireland’s creation was difficult for unionists, however: it represented the demise of all-Ireland unionism, and some mourned the loss of Cavan, Donegal and Monaghan – three of Ulster’s nine traditional counties – from the new six county statelet. While Craig had sought security for his people, Northern Ireland came to face the continuous challenge of a constitution not designed for long term survival. Partition was never intended by the British as a permanent solution to the Irish question, and ultimately it would set the tone for decades of strained relations between unionists and Westminster. As we reflect upon the centenary of partition, it is interesting to connect the legacy of 1921 with the underlying constitutional uncertainty of unionist politics that runs like a thread throughout Northern Ireland’s 100-year history.

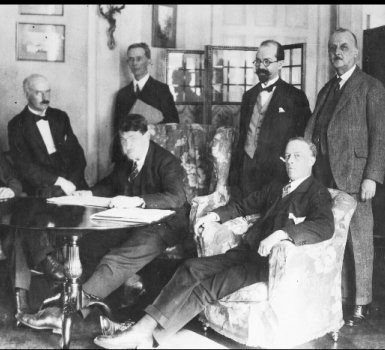

In December 1921, Ireland’s 26 counties were offered self-governing Commonwealth Dominion status in the Anglo-Irish Treaty. A minority of unionists looked at this as an attractive potential model for a more independent Northern Ireland. In the years that followed, the Irish Free State exercised its sovereignty – adopting a new constitution and renaming itself simply ‘Ireland’ or ‘Éire’ in 1937, and formally establishing itself as a Republic in 1948. Unionists, meanwhile, felt uncomfortable that Westminster retained the constitutional right to withdraw its support for Northern Ireland’s place in the Union. Faced with this perceived British indifference, Basil Brooke – Northern Ireland’s third Prime Minister – initiated discussions following the Second World War about whether the political and fiscal autonomy of Dominion status was a better option for Northern Ireland. Some party elites supported this idea, but the most significant counterargument was that it risked alienating the Unionist Party’s working-class Protestant support base. Combined with issues of financial viability, the Dominion discussion eventually dwindled.

This was not the last time that unionists considered alternative visions of Northern Ireland’s constitutional position, however. Flashpoints of crisis throughout the ‘Troubles’ conflict frequently saw proposals for different arrangements coming to the fore. These included full integration of Northern Ireland with the UK, the creation of a federal UK, the repartition of Ireland, and independence for Northern Ireland. These proposals were all pitched as opportunities to strengthen or stabilise Northern Ireland, reflecting deep rooted unionist insecurities that the 1920 Government of Ireland Act had not gone far enough to secure unionist interests.

The proroguing of Stormont in 1972, the Sunningdale Agreement of 1973, and the Anglo-Irish Agreement of 1985 were traumatic to vast swathes of the Protestant unionist population. The 1993 Downing Street Declaration echoed Attlee’s 1949 Ireland Act in underlining the principle of consent, but its assertion that the British government had no ‘selfish strategic or economic interest’ in Northern Ireland caused great unionist disquiet. Each was an unwelcome reality check as to Northern Ireland’s subordinate status to the exigencies of Westminster strategy. In 1972, Canadian-born academic Kennedy Lindsay – a prominent proponent of independence for Northern Ireland– echoed the words of 19th century constitutional lawyer A.V. Dicey, a critic of Gladstone’s initial proposal of Irish Home Rule, when he wrote ‘A local parliament for one region only and subordinate to the Imperial Parliament cannot be a permanent solution’. To Lindsay, this is exactly what had been delivered for Ulster in 1921.

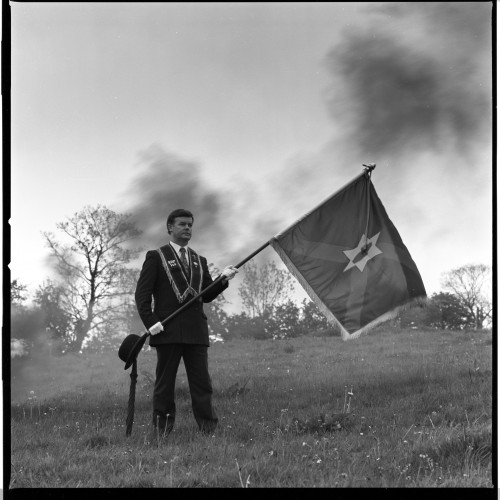

While it never held a notable electoral mandate and was usually relegated to the political fringe, independence is still perhaps the most significant of these alternative constitutional proposals in that it comprised a diverse, active movement during the conflict, spanning individual activists, small political parties and strong sections of support within Vanguard and the Ulster Defence Association. Different versions of an independent Ulster competed under the umbrella of the Ulster nationalist movement. Kennedy Lindsay revived calls for Dominion status, with the maintenance of British links through the Commonwealth and the Crown, while the UDA-aligned New Ulster Political Research Group modelled their vision of independence for Northern Ireland’s six counties on the United States and were neutral on Commonwealth membership and monarchy. The Ulster Movement for Self-Determination, which emerged from the anti-AIA Ulster Clubs in 1986, had even advocated for an enlarged state that reincorporated the three Ulster counties ceded to Southern Ireland in 1921. There were also different approaches as to how independence might be achieved. During the early 1970s and around the Ulster Workers’ Council strike, some in Vanguard had flirted with a Unilateral Declaration of Independence to put pressure on the British Government, while the NUPRG advocated for negotiated independence and emphasised how a pluralist Ulster state could build consensus between Protestant and Catholic people.

The independence movement claimed a small historic lineage, pointing to a number of predecessors like W.F. McCoy, elected as Ulster Unionist MP for South Tyrone in 1945. Electoral posters published by the British Ulster Dominion Party during the 1970s – the party of the aforementioned Kennedy Lindsay – endorsed James Craig as the founding figure of their movement, featuring the slogan ‘Lord Craigavon was right! Ulster has the Dominion alternative’. This was a reference to Craig having suggested to Lloyd George during Anglo-Irish Treaty negotiations that Dominion status would be preferable to inclusion in an all-Ireland parliament. Whereas those previously contemplating Dominion status had been Unionist Party elites, calls for independence during the ‘Troubles’ generally came from the anti-establishment loyalist grassroots. It was precisely their distance from the halls of power, and lack of dependence on electoral approval, that gave paramilitaries and small political groupings the freedom to pursue an agenda of independence.

While recent unionist protest against the Northern Ireland Protocol in the context of Brexit has not seen a revival of calls for Ulster Independence, the fundamental themes of constitutional insecurity and perceived British untrustworthiness that accompanied Northern Ireland’s foundation still resonate. One legacy of partition, and the institutions that it established, has been the unsettled nature of unionist politics, and the repeated unionist frustrations under a British solution never intended to secure their lasting self-determination.

James Bright, University of Edinburgh