Health services in post-partition Ireland: Diverging trajectories and differing systems

08 November 2021

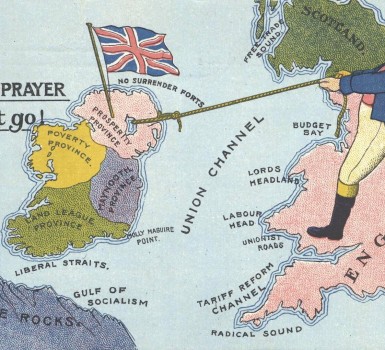

On 5 July 1948 the Northern Irish government introduced the Health Services Act on the same day that the English, Welsh and Scottish National Health Service acts came into effect. This heralded the introduction of a nationalised, universal and free health service funded primarily out of general taxation – a watershed moment for Northern Ireland and the U.K. The NHS became a key component of U.K. post-war reconstruction and on either side of the border in Ireland, its introduction marked the divergence of two significantly different health systems.

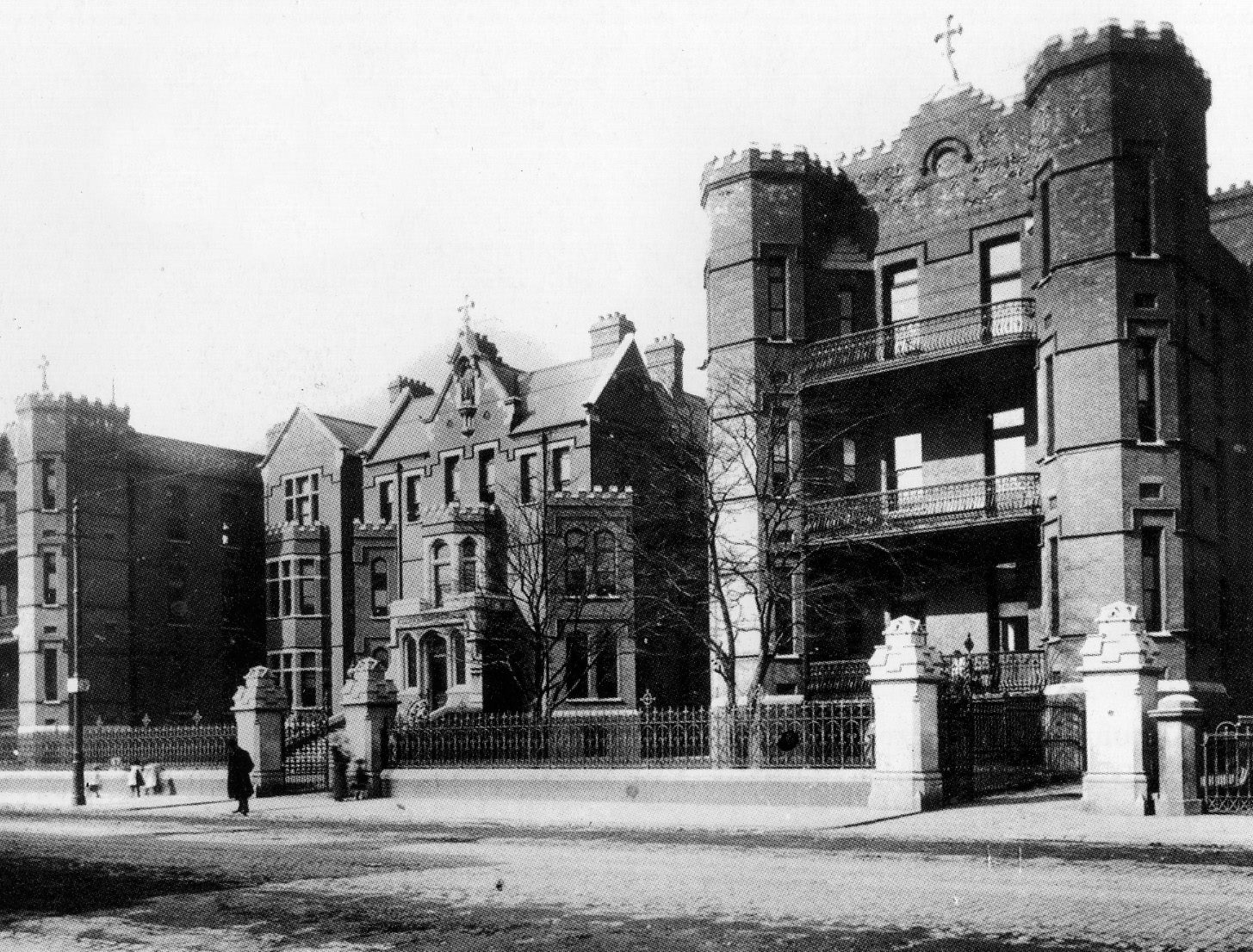

Prior to the NHS’s introduction in 1948, the Northern Ireland devolved government’s record in health policy was poor. High mortality and morbidity rates, especially amongst infants in Belfast, were an indicator of an unhealthy population. Health services were provided by a mixed economy of voluntary, poor law and municipal authorities, and often marked by parsimony with little integration, planning or central government involvement. A key failure of the inter-war Northern Irish government was the lack of reform of the stigmatising workhouse system which tied medical care to the relief of poverty.

Another factor that undermined health services during the early decades of Northern Ireland was the failure to establish a stand-alone government department responsible for health until the creation of the Ministry for Health and Local Government in 1944. Up to this point health services were under the auspices of the Ministry of Home Affairs which was also responsible for, and often preoccupied with, internal security.

By the 1940s there was greater appetite for health reform but plans to introduce the NHS were met with resistance from some within Ulster Unionism who were fearful of socialistic measures from the Labour Westminster government. Initial opposition, however, soon dissipated with the rapid expansion of health services which were by-and-large funded by London.

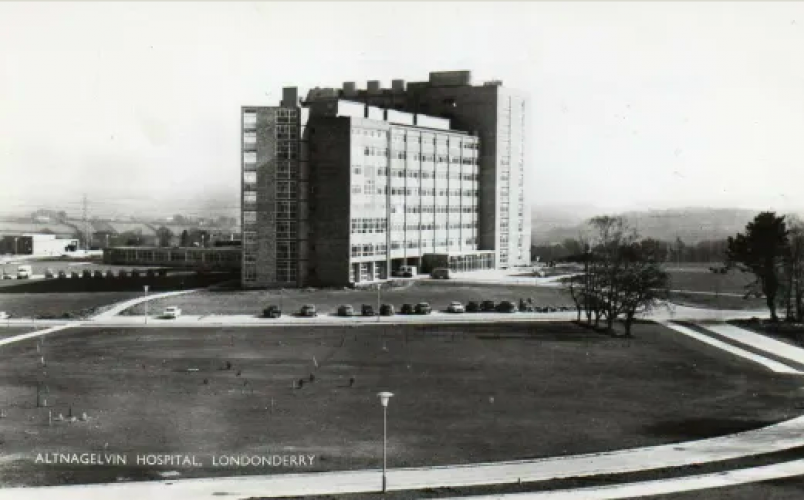

Under the auspices of the Northern Ireland Hospitals Authority an ambitious hospital building programme was commenced. This contrasted with Britain’s experience where the NHS’s first decade was marked by little capital investment; remarkably, the 1955 Tanner Committee on Northern Irish health services noted: ‘nothing approaching this scale of expansion and improvement [had] yet been possible in any Hospital Region in Great Britain’.

Altnagelvin Hospital, which opened in 1960 in Derry, was the cornerstone of Northern Ireland’s hospital programme. The first purpose-built hospital in the U.K. under the NHS, Altnagelvin was a revolutionary multi-story building and designed by the London-based Y.R.M. firm which was key to the architectural modernism of the nascent British welfare state.

The expansion of health services in post-war Northern Ireland gave the impression of a modernism based on planning and value-free technocratic expertise; however, the old political and religious tensions were never far from the surface. The incapacity of successive Northern Irish governments to accommodate the Mater Infirmorum Hospital in Belfast – a Catholic voluntary hospital – until the early 1970s led to Catholic and Nationalist discontent. Yet the universalism of the health services helped to ensure their popularity.

In the South of Ireland partition led to attempts at reform of the health services. The Free State replaced the poor law and workhouse system with a new layer of county and district hospitals. Such reforms were not insignificant and predated similar measures in Britain in 1929 while workhouses remained in Northern Ireland until the 1940s. The establishment of the Irish Hospitals Sweepstake in 1930 was designed to meet the financial crisis which threatened to cripple voluntary hospitals. By 1940 the Sweepstake had generated close to £4 million for voluntary hospitals and £2.5 million for county and district hospitals. While this represented unprecedented investment, the Sweepstake also had a less positive long-term impact. The funding strengthened voluntary hospitals’ independence from state influence, closely connected to the medical profession and the religious hierarchy. Voluntary hospitals were nationalised in the U.K. under the NHS, but they continued in the Republic of Ireland where to this day many hospitals maintain their voluntary ethos, even if the structures of funding and management are integrated with the state.

The Sweepstake funding also solidified the county as the unit for health organisation despite attempts to introduce more effective regionalised healthcare structures which were not introduced until the 1970 Health Act. In contrast to developments in the South, the NHS was organised regionally to allow for the integration of services. Regional Hospital Boards were established in Britain while in Northern Ireland hospitals were grouped together under hospital management committees. Yet such structures did not provide the ideal equilibrium between central, regional and local management envisaged at the NHS’s inception and the health services have been the focus of much subsequent reform.

The role of the Catholic Church took ever-greater precedence in southern Irish medical policy, particularly in maternity and child welfare and moralistic concerns about state intervention in family life encouraged much social inaction. Attempts to increase state healthcare led to conflict between the state, Catholic hierarchy and medical profession, as demonstrated in the Mother and Child Scheme debacle. Plans to introduce free primary care for mothers and children were successfully opposed by religious and medical authorities, who feared socialised medicine and nationalisation, which resulted in the resignation of the then minister for health, Noël Browne, and the subsequent fall of the Fine Gael-led coalition government in 1951.

A free and universal health system was never fully introduced in the Republic. The establishment in 1957 of the Voluntary Health Insurance Board, a semi-state private insurance body, popularised private medical insurance for hospital and consultancy services. Ireland’s health services developed into a ‘mixed’ system of providers – public, voluntary and private – where entitlement and eligibility varied from service-to-service. A private-public dichotomy emerged and access to healthcare was often shaped by ability to pay health insurance, which contrasted greatly to the free NHS in Northern Ireland.

Healthcare in Ireland since partition has taken different trajectories in the two political entities. Prior to 1948, independent Ireland demonstrated the greater appetite for health policy innovation evidenced in poor law reform and the Irish Sweepstake. Yet the introduction of the NHS in Northern Ireland radically altered the province’s health services. Predicated on principles of nationalisation and universalism which emanated from Westminster’s post-war Labour government, the NHS developed as one of the few U.K. institutions that somewhat transcended political and religious divides in Northern Ireland. Contrastingly, the Republic’s health system continued to be marked by various providers, religious involvement, and a complex inequitable two-tier system which up to the present day has failed to garner popularity.

Dr Sean Lucey