Remembering Terence MacSwiney in the Irish diasporic built environment

30 November 2021

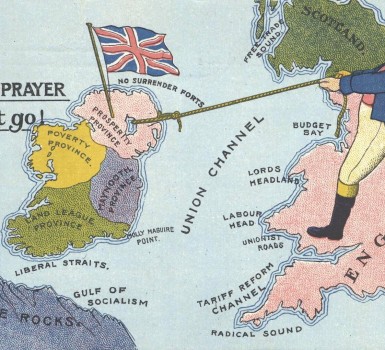

The outbreak of the Irish civil war and the establishment of a new Northern Ireland state in 1921 sent Irish diasporic communities into confusion. Diasporic engagement with Irish politics had always been diverse. Support for home rule dominated across the British Empire while more militant nationalist activities had a long history in the United States. The execution of Easter Rising leaders in 1916 had prompted a shift in some diasporic communities towards Irish independence, particularly in areas which had traditionally focused on constitutional change.

In Melbourne, Archbishop Daniel Mannix led the way. The 1918 St Patrick’s Day parade saw Sinn Féin colours and flags displayed alongside Australian and papal flags while the 1920 parade was a grand demonstration of both Australian war service and support for Ireland in the War of Independence. The following year, the flag-bearer holding the Union Jack was rushed by angry men who attempted to take the flag. While the official parade was banned in 1922, an unofficial one took place with Mannix at its helm. In Chicago, parades had largely given way to banquets and balls under the guise of not wanting to spend money unnecessarily.

The conflict in the aftermath of the Anglo-Irish Treaty threw the allegiances of Irish ethnic communities, made up of those of Irish birth and descent, into disarray. International lecture tours reduced in number, splits surrounding the Treaty found their way into the make-up of parades and banquets, and amidst the confusion, public demonstrations in support of Irish nationalism soon petered out. When there were celebrations of Irish nationhood or ethnic community, the focus shifted away from conflicting feelings regarding partition and the Free State, towards general expressions of hope and peace for the Irish Free State. Instead of public displays of support, therefore, it is useful to turn to the built environment to consider the long-term remnants of Irish partition, the War of Independence, and civil war memory in the diaspora.

In 1893, two Irish ‘villages’ were set up in the centre of Chicago. These villages presented Ireland as a rural idyll filled with comely Irish ladies making Irish handcrafts, and were part of the Chicago World Exposition (see Shahmima Akhtar’s work for more). One visitor to the Exposition was Thomas O’Shaughnessy, an Irish Chicago artist, and the portrayal of a medieval Ireland would having a lasting effect on how Ireland was represented within Old St Patrick’s Church, the oldest still-standing Catholic church in Chicago.

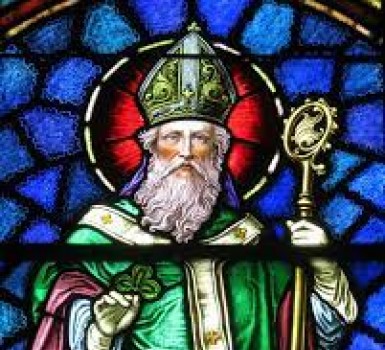

From 1911, O’Shaughnessy transformed the interior of St Pat’s to reflect the parish’s historic Irish-American congregation. The effect of his 1906 trip to see the Book of Kells in Ireland, and the wider Celtic Revival movement, can be seen on the walls, decorations and stained glass of the church. This invocation of medieval Ireland was not unusual in diasporic Irish circles, the colonial experience of Ireland glossed over to hark back to a medieval Ireland filled with balladry, chivalry, and education.

This relatively neutral engagement with Irish nationalism was particularly important in a city like Chicago, where in-fighting over the direction of Irish nationalism, including support for the Irish-American Dynamite Campaign (1881-5), had led to public disputes between Irish nationalists based in Chicago and Ireland. The schisms within Chicago’s Irish nationalist circles came to a head with the sensationalised murder of Dr Patrick Henry Cronin in 1889. The 1890s and first decades of the twentieth century saw debates surrounding Irish nationalism retreat behind closed doors - apart from a brief interlude during the Boer War. However, by the time that O’Shaughnessy was close to completing his work, this focus on the medieval had shifted. Events in Ireland had overtaken the need for Chicagoan neutrality.

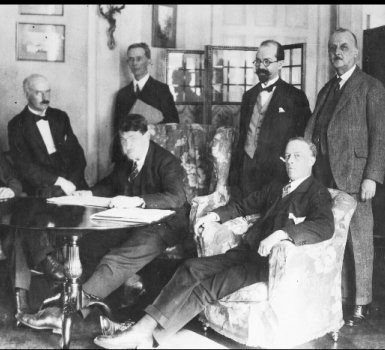

One of the focal points of St Pat’s are the three massive stained glass windows on the eastern wall. The central window is entitled ‘hope’ and is also known as the Terence MacSwiney window. This is due to the panel at the bottom (figure 2). Completed in 1922, this panel features Lord Mayor of Cork Terence MacSwiney – who died on hunger strike in Brixton Prison in 1920 – ascending to heaven surrounded by angels while the panels to either side show the chaos and horror of the world below. This window explicitly aligns the church with Ireland and Irish nationalist activity.

Though St Patrick’s Church remained a Catholic space throughout the twentieth century, its Irishness fluctuated based on demographic and zoning patterns. It was only when its Catholicism was at risk – with a dwindling congregation, the church was at risk of sale – that Old St Pat’s became an Irish church again. A community-funded restoration of the interior and exterior was carried out during the 1990s, giving a new lease of life to the community memory of Terence MacSwiney. Emblazoned on the church’s central window, MacSwiney became a focal point: a lasting legacy of Chicago’s engagement with the events of the early 1920s.

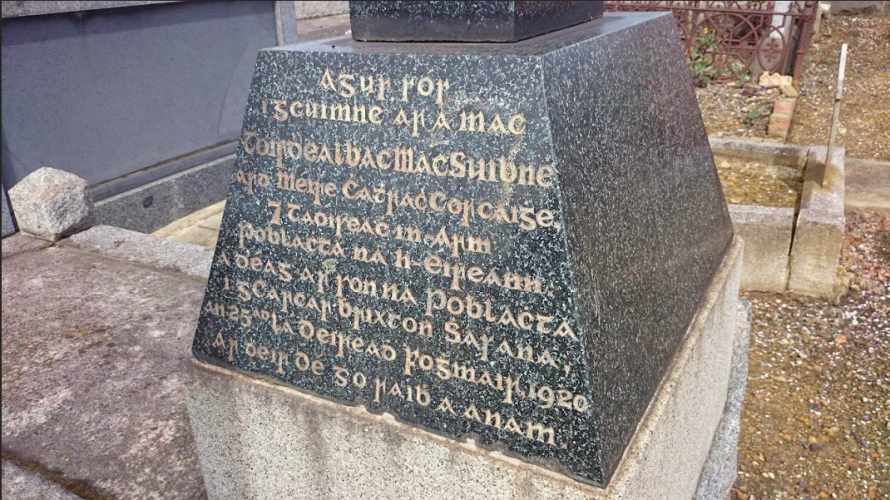

In Melbourne too, Terence MacSwiney found his way into the built environment. John MacSwiney, the father of Terence, died in Melbourne after emigrating from Ireland in 1885. After Terence MacSwiney’s death in 1920, additions were made to John’s grave-marker in Melbourne General Cemetery. In Irish, the marker now declared that ‘In memory of his son Terence and Mayor of Cork’ who died for the ‘Irish republic’.

With this addition, a moment in twentieth-century Irish revolutionary history was added to a religious but relatively inclusive site. Terence MacSwiney is remembered in the same space as other Irish political prisoners, like Cornelius O’Mahony (died 1879) and Hugh Brophy (died 1919), both of who had ‘released political prisoner of 1867’ inscribed on their grave markers. As diasporic communities struggled to understand the complexities of a partitioned Ireland thrown into civil war, small symbols in the built environment allowed for the claiming of a particular history and legacy.

We frequently think of parades, statues and plaques when considering the memorial of revolutionary periods. However, the legacies of the Irish Revolution often made their way into the diasporic built environment in more subtle ways: an addition to a family member’s grave marker or a pane of glass in a church window. As debates around statues have demonstrated, these memorials in the built environment can mean a lot to those in the know but often fail to register in the symbolic landscape of other people. These contemporaneous memorials to the Irish revolution may fall out of fashion, but they can allow us to track shifting diasporic engagement with important moments of Irish history.

Dr Sophie Cooper, Queen's University Belfast