Sowing the Fourth Green Field: Michael Collins' Northern Policy, January-August 1922

21 March 2022

Approaching the centenary of his death, Michael Collins remains a divisive and controversial figure. Soldier, statesman, democrat, dictator, patriot, or traitor are contradictory interpretations of Collins which are particularly relevant as society reflects on 1922. One of the most recurring themes in relation to remembering Collins concerned how commemorative and literary efforts emphasised his republican militancy or democratic state-building role. More broadly representative of militarism and moderation, these aspects of Collins’ career were blurred between January and August 1922 when he adopted policies of ‘non-recognition, diplomacy and coercion’ towards Northern Ireland.

After the Treaty, connections between North and South had become increasingly strained, historically established divisions had intensified. More fatalities occurred in Northern Ireland during the first seven months of the truce than in the entire preceding Anglo-Irish War. Riots, burnings, and sectarian murders were daily occurrences. In January 1922, Collins had insisted that the Treaty would lead to ‘good will’ between the partitioned states. But the following month Collins funded 800 teachers in 270 schools which refused to recognise Northern Ireland’s legitimacy. Eoin O’Duffy, Collins’ subordinate and confidant, informed a Clones IRA meeting in February that Collins signed the Treaty as ‘a trick’ to collect British arms and continue the struggle for a united Irish Republic. ‘Partition will never be recognised’, Collins personally informed the northern IRA, although ‘it might mean the smashing of the Treaty’. Conflicted incidents as such confirm the complexity of Michael Collins’ northern policy. Defending the Treaty democratically, funding a non-recognition policy, whilst organising the first IRA attack on Northern Ireland, questions his interpretation of the Treaty and faith in the Boundary Commission.

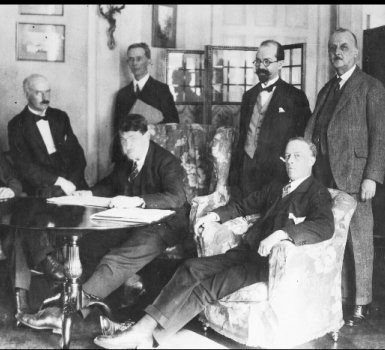

THE CRAIG-COLLINS PACTS

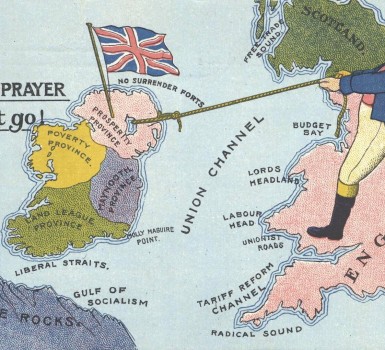

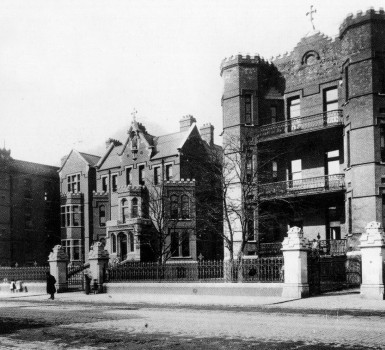

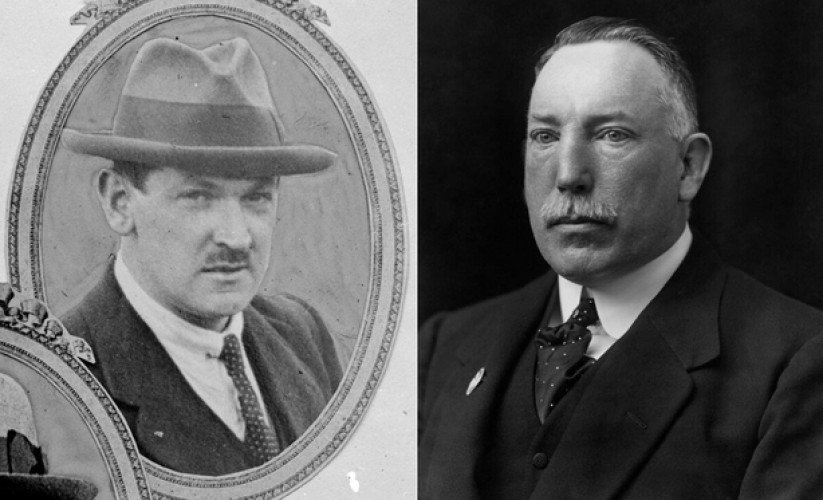

As Chairman of the Provisional Government, Collins met Northern Ireland’s premier, Sir James Craig, on three occasions between January and late March 1922. Two political pacts were concluded. Agreeing to abandon the Belfast Boycott (a scheme designed to make the north-east aware of its southern economic dependence) Collins, at Craig’s suggestion, also agreed to abandon the Boundary Commission. Alternatively, the two governments would appoint representatives to address the border issue. Craig would attempt to reinstate expelled Catholic shipyard workers. The agreement failed in its objectives, neither Craig nor Collins fulfilled their obligations. But for James Craig, the agreement secured Collins’ recognition of Northern Ireland, and confirmed that the Treaty’s partition clauses could be amended. On 2 February 1922, Collins and Craig met again. During this encounter, their conflicted interpretations of the Boundary Commission were revealed. Collins was convinced almost ‘half the area’ of Northern Ireland would join the Free State, whilst Craig believed that minor border adjustments would be made; Craig vehemently argued that locations of historic unionist significance, such as Derry and Enniskillen, could not be forfeited. While Collins had viewed North/South negotiations as a means of persuading Craig of the benefits of Irish unity, he misinterpreted Craig’s key objective, to eradicate the Boundary Commission.

For Collins, the formation of Boundary Commission to adjust the border (created by the 1920 Government of Ireland Act) to the wishes of the inhabitants, would render the northern state unviable due to the Catholic majorities in Derry City, ‘South and East Down, South Armagh, Fermanagh, and Tyrone’. Famously, Collins interpreted the Treaty’s boundary clauses as ‘a means of inducing unity by territorial contraction’; but, in various capacities, the problem with the Boundary Commission’s proposals lay in their vagueness and ambiguity. Historians have questioned why the Irish delegation did not insist upon a plebiscite to readjust contested areas or gain increased clarification to what was meant by border amendments being made according to ‘economic and geographic conditions’. The Treaty’s seemingly ‘outward expression of Partition’, as Collins admitted, had disappointed northern nationalists, but those situated in border regions had been consoled by Collins’ assurances that the Boundary Commission would deliver them to the Irish Free State.

COUNTER MEASURES

As IRB President and IRA Director of Intelligence, Collins’ previous Anglo-Irish War experience had conditioned him to use force, often without consideration of its reverberations. In February 1922 he attempted to secure the release of the ‘Monaghan Footballers’, IRA men captured with arms in Tyrone, and three republicans awaiting execution in Derry. Dispatching two IRA men on an aborted mission to England to kill the hangmen, Ellis and Willis, Collins, on the advice of his subordinate, Eoin O’Duffy, also advocated the kidnapping of forty three prominent unionists on 7 February 1922. Although some of the assailants were captured in Free State uniform, Collins, who the unionist press deemed ‘a gunman’ and ‘conjuror’, avoided suspicion of involvement. Sectarian violence had escalated after the kidnappings. Following the ‘Clones Affray’, an incident in which an IRA commander and four Specials were killed, a bomb was thrown into a group of Catholic children, killing six and injuring others. In total, forty-three people had been killed in February 1922. Responding to the introduction of the Special Powers Act and suppression twenty nationalist controlled councils, which refused to recognise Northern Ireland’s legitimacy, Collins organised IRA border raids. He established a military force, comprised of both pro and anti-Treaty IRA members, known as Northern Command, the Ulster Council or Northern Military Council, to coordinate IRA attacks in the six counties. A range incidents, shootings of Ulster Special Constabulary members and barracks attacks occurred along the border from March. These confirmed that Collins was simultaneously negotiating with the British Government and attacking its territorial interests.

Reprisal and counter-reprisal followed; 103 people had been killed in Belfast alone between February and March 1922. From 18-26 March, thirty died and thirty seven were wounded. According to Lloyd George, Collins, ‘who would talk of nothing else’ had ’become obsessed’ with the northern situation and behaved like a ‘wild animal-a mustang’ while discussing anti-Catholic pogroms. In retaliation for the killing of two of their officers, five members of the Catholic McMahon family and a barman were shot dead by the Ulster Special Constabulary. Collins regarded the Specials as ‘violent Orangemen’, who were following the orders of the Northern Government’s Security Advisor- ‘Sir Henry Wilson’.

After Churchill summoned Collins and Craig to London, a second agreement was signed on 30 March. Among various points, Collins and Craig had agreed that the Boycott would end, the two governments would collaborate to restore peace, the creation of a half Catholic, half Protestant police force, and a pledge that IRA activities in Northern Ireland would cease. But violence continued. Coinciding with the split in the IRA into pro and anti-Treaty factions, the anti-Treaty IRA quickly reimposed the Boycott to undermine Collins. In further reprisal for the killing of a USC member, five Catholics were murdered in Belfast’s Arnon Street. North/South relations deteriorated; Craig remained inflexible; within a month, talks broke down. Disagreements, allegations, and recriminations for its failure would linger for months. Publicly, Collins attempted to ensure Craig would fulfil his obligations. He made various appointments to Pact committees. Without the knowledge of his Provisional Government colleagues, he ordered a republican offensive in Northern Ireland.

NORTHERN OFFENSIVE

Collins was aware that opposition to partition was ‘the one common platform’ on which all Irish nationalists could stand. He was also conscious that the requirement to protect northern nationalists could unite the pro and anti-Treaty divide in a common cause. By adopting a militant northern strategy, Collins was enabled to protect northern nationalists, undermine Craig’s government, and delay a split in the IRA. Collins supplied southern anti-Treaty IRA units with arms which the British provided to the Provisional Government, who in turn sent their untraceable weapons to the northern IRA. Collins duplicitous northern strategy had intensified from April 1922, the most significant example of which was the failed IRA offensive that began on 18 May. Consisting of arson, attacks on barracks, stately houses, and railways, this campaign involved sectarian outrages against the Protestant community, provoked anti-Catholic retaliation, and resulted in the introduction of internment in Northern Ireland.

Between spring and early summer, the Treaty divide had deepened, Collins’ relationship with the anti-Treaty IRA had irrevocably soured, contention with London had increased. Churchill feared that republicans would seize power as a result of the Collins/De Valera electoral Pact. This had proposed that the two wings of Sinn Féin would appoint a united panel of candidates and form a coalition government. Originating from the concerns of a northern delegation. Collins and De Valera had been warned of the ‘grave danger’ of permanent partition’ and possibility of ‘national disaster’ if civil war was not averted. The Collins/De Valera Pact angered Craig; he insisted he would not be participating in the Boundary Commission ‘under any circumstances whatever’.

Due to the ineffectiveness of Collins’ northern policy and the pressing nature of the Irish Civil War, Collins had reverted to a conciliatory northern policy by late June 1922. Publicly, he maintained that he would not coerce the region and advised the northern nationalist population to uphold the non-recognition policy; the IRA would provide an exclusively protective role. Northern IRA leaders were assured by Collins that the Ulster question would be addressed in the near future. As Collins retained the northern IRA divisions and continued to train the IRA in guerrilla methods suggested that he planned further military action in Northern Ireland.

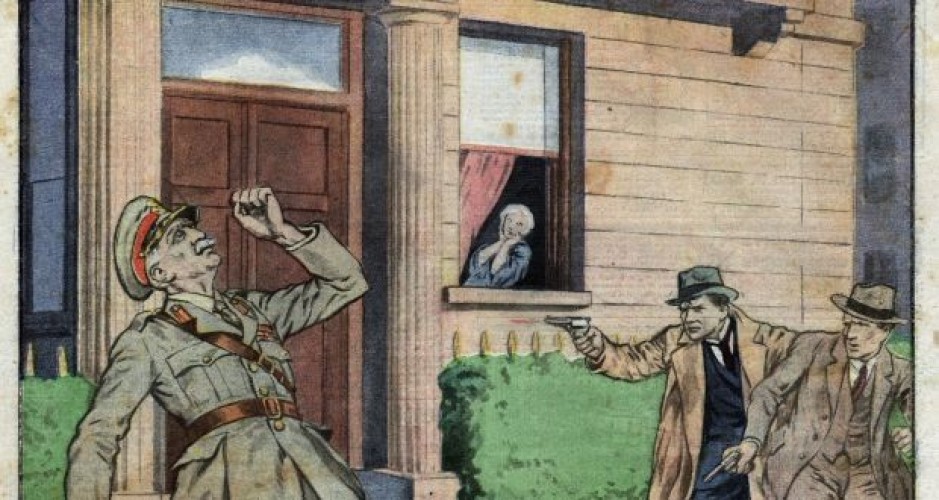

On 22 June 1922, Sir Henry Wilson was shot dead in London. Since his appointment as northern advisor, Wilson had criticised political engagement with Collins. In Collins’ view, ‘Wilsonian militarism’ was responsible for the anti-Catholic pogroms in the north; he considered his death a boost for the demoralised northern IRA. While anti-Treaty republicans were blamed for his assassination, it is widely accepted that Collins gave the order before the truce. Wilson’s killing, and the impending British pressure to vacate the Four Courts had forced Collins to initiate the Irish Civil War. Collins, then Commander-in-Chief of the Free State Army, believed that Specials, under Wilson’s direction, were attempting to provoke a republican reaction that would deflect attention from northern atrocities and justify the British ‘reconquest of Ireland’. But it also has been argued that Wilson’s assassination ‘was of a piece’ with Collins’ northern policy since January 1922 and requires to be viewed in light of the sustained and impassioned emphasis he placed on partition prior to his death in August 1922.

Even before his death, Collins’ Provisional Government colleagues attempted to reverse his ‘belligerent’ northern policy before his death. Considering it counter-productive, the Provisional Government created a report, ‘subject to obtaining the approval of the Commander-in-Chief’ that proposed that ‘all military operations’ in ‘or against the North-East’ should cease in order ‘to acknowledge’ the ‘authority’ of the Northern Irish state. It is unknown if Collins had considered the proposals. He was killed only three days later at Béal na mBláth. Resultantly, after the scrapping of the Border Commission’s findings after Collins’ death and the maintenance of the Irish border, his northern policy and views on partition were increasingly susceptible to interpretation, adaption, and myth.

Dr Conleth McCloskey