Myth, Memory and Community: Loyalist Great War Remembrance

01 July 2021

Gareth Lyle, University of Edinburgh.

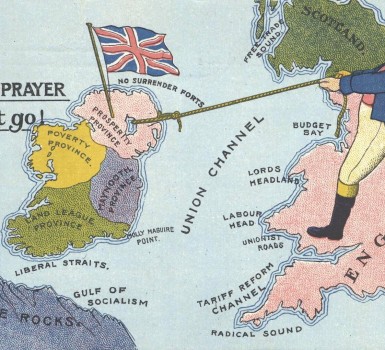

For Ulster Loyalism, a political dimension informs memory of the Great War, and central to this is the 36th (Ulster) Division, regarded as 'theirs'. The association emanates from the belief that the Ulster Division consisted entirely of the Ulster Volunteer Force, created in 1913 to counter the threat of Home Rule. Research shows around 30% of the original UVF joined the Ulster Division.

The UK declared war on 4 August 1914, but the Ulster Division was not formed until September. UVF members joined other regiments. Many were reservists and thus returned to their original units, with the UVF losing 4,350 reservists. Impatient with the delay, others enlisted wherever they could. In Belfast, many men joined the 2 Battalion Royal Irish Rifles or the Norfolk Regiment.

Contrary to popular memory, many UVF men did not enlist in the war. Some were reluctant to fight or feared the threat of potential Nationalist attacks if the UVF were not present to defend Ulster or if Home Rule was imposed.

Gauging accurate numbers of UVF membership is difficult. For example, the East Belfast UVF claimed a membership of 10,000 in 1914, but the average turnout for parades, inspections and training camps was around 3,500-4,000; when the battalion became 8 Battalion Royal Irish Rifles, only 1,000 men enlisted at the recruiting office.

Yet despite these facts, the Great War is still central to Loyalist memory. Key to that is the Somme: 5,500 casualties were incurred over 1-2 days including men who were killed, wounded and missing.

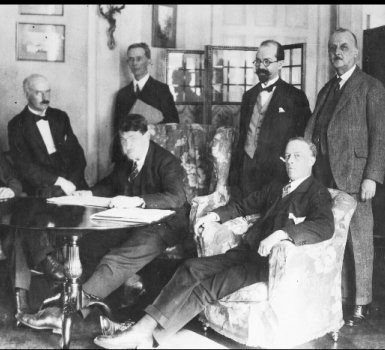

As early as the aftermath of the battle the dead from the Somme were quickly linked to Protestant losses at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. For Loyalists, the link between the Boyne and the Somme is that both were fought for 'freedom from tyranny'. Imperial Germany was deemed as being no different from James II. Different chronologies were interwoven to cater to the perceived needs of the present. At the 1919 Twelfth there were memorial arches honouring the war dead. Ulster Unionist leaders were involved in organising commemorative events; commissioning JP Beadle's portrait of the Ulster Division for Belfast City Hall (1918), building the Ulster Tower at Thiepval (1921) and inaugurating the Belfast Cenotaph (1929). The officially endorsed history of the Ulster Division was written by Cyril Falls ('The History of the 36th Ulster Division', 1922). It can be read either as military history or as Unionist propaganda, written to ensure the Loyalist sacrifice was never forgotten.

By the mid-1930s Loyalist memory consolidated, remaining static for the next thirty years. Physical memorials were erected in urban spaces, churches, schools, workplaces and sports clubs, offering a constant reminder of the war.

Yet this began to change amidst the civil unrest that broke out in N. Ireland during the 1960s. With tensions rising, the UVF was resurrected by, amongst others, Gusty Spence, a former soldier and leading Belfast Loyalist. By using an established “name”, Spence was deliberately invoking the memory of the Great War by resurrecting the UVF. The two were interlinked. From the late 1980s the modern UVF were co-opted into the Boyne-Somme narrative, as UVF men joined the former dead as volunteers "killed in action". Billy McFadzean, a UVF man and winner of a posthumous Victoria Cross at the Somme, is often pictured beside modern paramilitaries on murals.

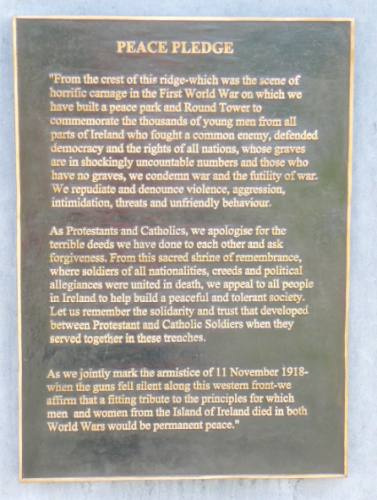

After the 1994 ceasefires, a more general shift in attitude towards the War took place across Ireland and the idea began to emerge of “shared suffering”: that Irishmen fought and suffered together. This developed into the “reconciliation approach”, an attempt to use the comradeship of the war to bring present day communities together. Its ultimate expression was the creation of the Messines Peace Park, commemorating all those from Ireland who died in the Great War. This idea found some traction within Loyalism: indeed there are photos showing UVF delegations at Messines, but not all Loyalists welcomed this. Whilst Loyalists may happily visit the Peace Park, for some, the real focus of commemoration on the Western Front always centres around the Somme.

The Ulster Division initially recruited from specific localities, often where relatives of these men still reside. Commemoration of the war is an intensely personal affair, as the dead of the Ulster Division were not simply Irish troops, but relatives or friends. Loyalists may accept the service of Irish Nationalists without qualms, but that does not mean they are also prepared to take ownership of the Nationalist war dead.

Loyalist memory of the Great War is as much about present-day needs as it is the past. It is a collective recollection of a traumatic period that encompasses the War, the near civil war over Home Rule, and the violence that created Northern Ireland. Yet it is constantly responsive to the contemporary circumstances. As the dead of the Easter Rising are revered by Republicans as an integral part of their struggle, so too are the Loyalist war dead martyrs in Northern Ireland’s creation myth.