Women in 1921: Politics, Revolution and Violence

02 July 2021

Dr Margaret Ward, Hon. Senior Lecturer in History at Queen’s University Belfast.

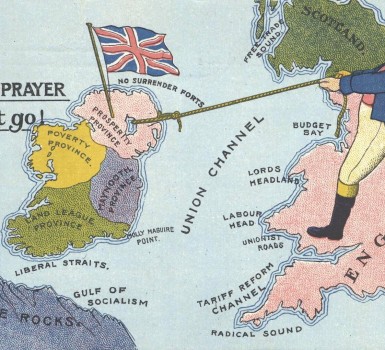

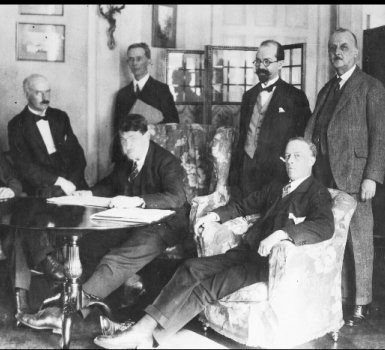

1921 was a year of huge significance for the whole island of Ireland. The Anglo-Irish war continued to be waged, but a Truce between the British government and Sinn Féin would be agreed in July. Before that, the Government of Ireland Act of December 1920 divided Ireland into six and twenty-six counties and elections for a parliament in the North took place in May 1921. While no sides to the conflict included women in their high-level negotiations, women did play significant roles throughout this period.

Republican Women

Cumann na mBan, the Republican women’s organisation, had started out by collecting funds, learning first aid and making first aid kits. However, as the war intensified their role increasingly became one of military support to the IRA.

In Ulster, where they operated in a situation where they had to contend not only with the Crown forces but with a hostile population, this supportive role was crucial. With the release of applications for military service pensions we now know much more about those women and their activities. This is a snapshot of some of their work during the months of 1921:

Weapons and Ammunition

In February Mary McClean took rifles from Leeson Street to Castle Street, supplying Volunteers who included Sean McEntee. She then carried a large collection of small arms and ammunition to McGraths in College Square North, to equip IRA members who had recently come to Belfast.

In April at least six Belfast women smuggled rifles and ammunition in golf bags by train to Cavan to supply an active service unit. Nellie O’Boyle, responsible for keeping open communications between the 3rd, 4th and 5th Northern Divisions, was one of those women, as an IRA commander verified, ‘whilst in possession of rifles concealed in a golf bag Miss O’Boyle was trapped in a cordon of British troops, but with great coolness succeeded in bluffing the troops and got the arms safely through.’

In May and June Teresa McDevitt brought arms, ammunition and despatches from Joe McKelvey and others to Charlie Daly and Eoin O’Duffy at their HQ in Draperstown. In June she also carried arms to Derry. James Heron of the Draperstown garrison said, ‘she carried arms for us through cordoned areas when it was impossible for us to do so ourselves.’

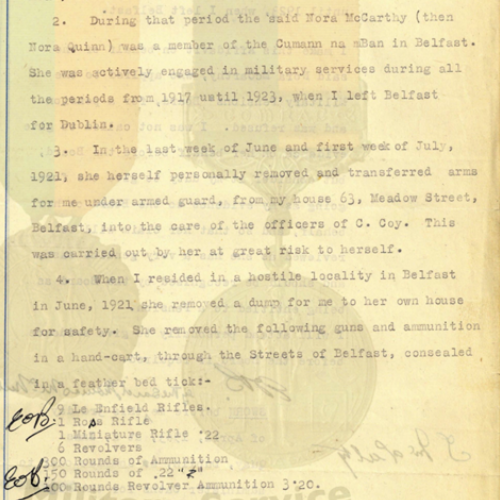

Thomas McNulty, Quartermaster of C Company Belfast IRA testified that Nora Quinn removed arms and ammunition when he resided in a ‘hostile locality’ and carried them ‘in a handcart through the streets of Belfast, concealed in a feather bed-tick’.

Dangerous and Varied Roles

Women often put themselves in direct danger by carrying out these tasks. Cassie McGuire of Omagh testified to her actions at an incident on 8 July:

I rendered first and under heavy fire from the enemy to a wounded IRA officer suffering from severe haemorrhage, being shot through the heart. All that night when the enemy retreated I was carrying two tins of petrol to a place of concealment. Next day our house was subjected to several raids, I managed at intervals to carry food to the IRA.

Indeed, women not directly involved with weapons or ammunition were often exposed to serious harm. Mona Delargy was one of the Cumann na mBan members who visited the Republican prisoners in Crumlin Road jail. Donegal man Denis Houston was met by Mona at the prison gate on his release on 11 July 1921. They travelled by tram to her home for a meal. Houston said he witnessed an ‘orgy of destruction and violence that will always remain in my memory. At one stage all passengers in the tram had to lie flat on the floor to avoid flying bullets and glass.’ After the meal, ‘Miss Delargy escorted me to the GNR station on the first stage of my journey back to Donegal and freedom’.

In Derry, where the military conflict was less intense in 1921, women like Cis Larkin and Roisin Horner were busy with clerical work, typing and distributing IRA GHQ orders, visiting prisoners in Derry jail, and carrying supplies of food and arms to units stationed in Donegal.

Unionist Women

In May 1921 six Republican women, all members of Cumann na mBan, were elected to the 2nd Dáil Éireann, while two Unionist women, Dehra Chichester in Derry-Londonderry and Julia McMordie in South Belfast, were elected to the first parliament in the newly created Northern Ireland.

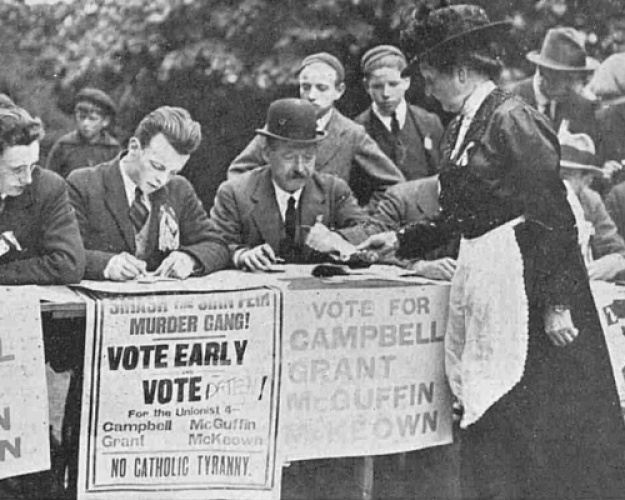

The Ulster Women’s Unionist Council had been organising against the threat of Home Rule since its formation in 1911. It had not supported women’s suffrage and although it had put forward some candidates for the 1920 local government election, when the time came for election to the first Northern Ireland parliament it declared that the time ‘was not ripe’ for women candidates because the essential issue was ‘to preserve the safety of the Unionist cause’. In their estimation women had not the necessary experience.

Instead, the council’s members devoted their energies to ensuring that women were on the electoral register and to canvassing for Unionist candidates. On election day, 25 May 1921, the Belfast News-Letter commented that ‘the women were exceedingly keen on the franchise … Hundreds of them were so eager to make sure of voting that they went to the polling places before 8 o’clock in the morning’.

Political Impact

After the election four hundred women who had worked for the return of candidates for the Cromac Division of South Belfast were presented with medals by Lady Craig, and a resolution passed, ‘That we wish to assure our PM Sir James Craig of our willingness to help and support him in whatever he sees fit to do for the welfare of our beloved Ulster and the Empire.’ Perhaps some of the women congratulated by Lady Craig had been motivated by a desire to ensure the election of McMordie, who was well known as a Vice-President of the UWUC and for her work as the first female member of Belfast Corporation?

After her election Dehra Chichester was congratulated by flute bands from all the nearby townlands who marched in procession to her residence in Castledawson. In thanking them she said, ‘They had saved their Maiden City – cheers – and please God, the old flag would never again be pulled from her walls.’

The English feminist paper The Woman’s Leader, in contrast, commented that Sir James Craig had remarked condescendingly that the men expected assistance from the women MPs ‘in minor matters, such as Poor Law’.

Julia McMordie’s maiden speech concerned the lack of women in the police force as only two out of three thousand police officers were female. She did not stand for re-election in 1925, preferring to return to local government. Dehra Parker (as she was known following her re-marriage in 1928) would be a long-standing member of the Northern Ireland parliament and the only woman to achieve cabinet rank.

A Time of Terror

For many other women, however, this was a time of terror as they became targets in this turmoil of military conflict and sectarian violence.

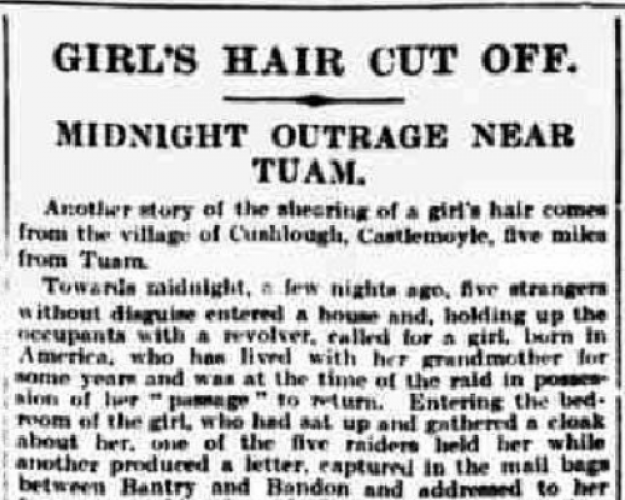

The American Commission on Conditions in Ireland, the White Cross and the British Labour Party all conducted inquiries into the state of the country in 1921. They found much reticence on sexual violence, although violence like hair cutting was used by all sides as a wartime tactic of punishment of women.

Sometimes women were subjected to brutal assaults for no other reason than their menfolk were absent, or as an additional act of violence when robberies were carried out. Not for nothing was this period also termed a ‘war on women’.