Breaking Away: Sport and Partition

22 April 2021

-1614293600.png)

Dr Ryan Mallon, Queen’s University Belfast.

On 9 April 1921, less than a month before the Government of Ireland Act was formally enacted, the British Home Championship football tournament and rugby’s Five Nations Championship came to a close.

Both competitions were ones to forget for Ireland. In rugby, the Irish side finished below Scotland on points difference at the bottom of the table, as England cruised to their seventh Championship and third Grand Slam success. It was Ireland’s second consecutive wooden spoon following the tournament’s post-war resumption in 1920, though a 9–8 victory over Scotland at Lansdowne Road in February at least avoided the prospect of two barren winless years.

The footballers fared even worse, losing all three matches with the team’s only goal coming through a late consolation from Jimmy Chambers in the final 2–1 defeat to Wales in Swansea. Nine years before the advent of the FIFA World Cup, and in an era without billionaire owners, brand management and breakaway Super Leagues, the annual tournament between the UK’s four ‘home nations’ represented the pinnacle of international competition, and Ireland’s poor performance drew stinging criticism from the local press.

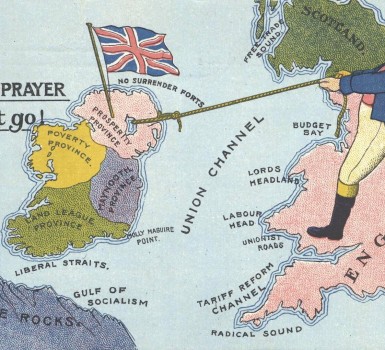

Despite the Irish sides’ lacklustre performances, the political symbolism of the two tournaments – contested by teams representing the whole island of Ireland – was strikingly apparent on the afternoon of 26 February, when Ireland’s football and rugby sides played host to Scotland north and south of what was soon to become the Irish border.

The Effects of Partition

The partition of Ireland in 1921 would have a major impact on how sport was organised on the island.

Boxing, cricket, golf and rugby decided to continue to govern on a 32-county basis. Despite partition, Irish home rugby games were shared between Dublin and Belfast until 1954, when eleven Republic-based players refused to stand for ‘God Save The Queen’ before their clash with Scotland at Ravenhill. It would be another 53 years before the Irish team played an international in Northern Ireland, a 23–20 win over Italy at Ravenhill in August 2007.

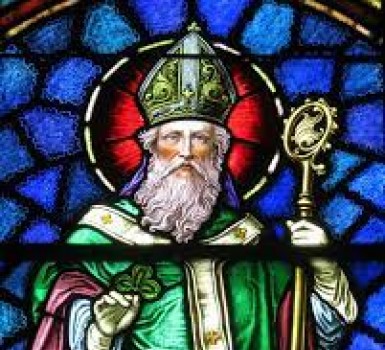

Gaelic games such as football, hurling, handball, and camogie – potent symbols of Irish cultural nationalism and often positively contrasted against ‘foreign’ sports such as rugby and soccer – also continued to be organised throughout Ireland. The Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) to all intents and purposes simply ignored the border. GAA members in the new Northern Ireland state viewed the growth of the games there as key to retaining strong links with the rest of Ireland: in the aftermath of partition the number of clubs in Ulster rose from around 100 to over 250 by the end of the 1920s.

Despite the onset of civil war in the 26 counties and the organisation’s often controversial policies, such as the banning of members playing ‘foreign games’ like rugby, the GAA was remarkably successful in creating a unifying sporting and cultural national identity, which effectively defied the new border.

Cycling: Protest in the Peloton

Other sports such as cycling endured a complicated series of disputes and splits after 1921. Governed by the GAA’s Athletics Council before partition, by 1922 organisation of both cycling and athletics had fallen to the all-island National Athletic and Cycling Association.

Tensions within this group – particularly over NACA’s rule, inherited from the GAA, which excluded British police and servicemen from membership – led to the first major split in Irish cycling along north-south lines in 1925, as what eventually became the Northern Ireland Cycling Federation (NICF) was formed. The NICF had close links with the National Cyclists’ Union of Great Britain – the forerunner of today’s British Cycling – and followed British rules on time trials and road races.

By the 1950s, there were three governing bodies for cycling on the island of Ireland: the six-county Northern Ireland Cycling Federation (NCIF), the 26-county Cumann Rothaíochta na hÉireann (CRE), and the republican 32-county National Cycling Association (NCA). Despite being by far the most popular of the three groups in terms of membership, the NCA was barred from international competitions due to rules which limited the administrative scope of national sporting bodies to within their established political borders.

Members of the NCA tended to be republican and anti-partitionist, and bitterly opposed the other two organisations, who accepted the jurisdictions imposed by the sport’s governing body. These tensions came to a head when NCA members staged anti-partition protests at the road world championships in 1955 and 1956, and at the Melbourne Olympics, where three NCA riders gate-crashed the start of the road race.

At the 1972 Munich Olympics another group of NCA riders illegally took part in the road race in protest against the political and sporting partition of Ireland. Noel Teggart, the sole Northern member of the actual Ireland team, was even pushed to the side of the road and held back as the peloton disappeared into the distance. The controversial stunt – personified by Teggart’s disconsolate reaction at the finish line – was roundly condemned in the Irish press.

Spurred on by the embarrassment caused by the Olympic road race, moves towards reunification of the three organisations began in the late 1970s, culminating in the creation of the all-island Federation of Irish Cyclists (now known as Cycling Ireland) in 1988.

However, the federation’s establishment split the NICF, and was boycotted by Unionist clubs who wished to retain their links with Britain. This stance was dropped in 2007, when the NICF rump finally amalgamated with Cycling Ireland. Ulster-based members of the post-Good Friday Agreement Cycling Ireland can still choose their preferred nationality on their racing licence, continuing cycling’s century-long association with Ireland’s complex political contours.

A Whole New Ball Game

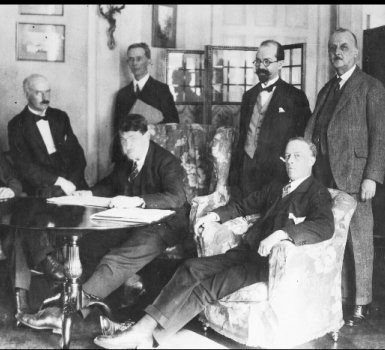

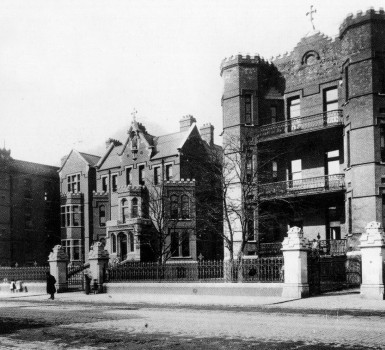

It is football, however, that has proved the most visible sporting reminder of Ireland’s political divisions. Just weeks before the new season’s British Home Championship was due to commence in October 1921, football in Ireland experienced its own partition. In September 1921 the Football Association of Ireland was formed as a Dublin-based counterpart to the Irish Football Association (IFA), located in Belfast and the original governing body for football on the island, founded in 1880.

The establishment of a rival national association was sparked by a dispute over the location of an Irish Cup replay between Glenavon and Shelbourne in April 1921. The match was originally scheduled to be played in Dublin but due to the worsening security situation due to the War of Independence, the IFA moved the game to Belfast. In the eyes of southern Nationalists, this decision was indicative of the body’s pro-Ulster bias.

In June the Leinster FA withdrew from the IFA, and three months later the FAI was born. A breakaway league and cup competition were quickly established. Meetings were held during the 1920s and early 1930s in the hope of reconciliation between the IFA and FAI, but without success.

The partition of football in Ireland was not straightforward and, initially at least, did not follow the political boundaries established by the Government of Ireland Act. Until the late 1940s, both associations claimed jurisdiction over the whole of Ireland, competed under the name ‘Ireland’, and selected players from north and south of the border. Between 1921 and 1950 38 players, including the Dublin-born Manchester United captain Johnny Carey, played for both Ireland sides as ‘dual internationals’.

With the two teams hoping to qualify for the World Cup, the prospect of players lining up for two different Irelands became increasingly incongruous. In 1953 football’s world governing body FIFA intervened and limited the jurisdiction of the island’s two football associations to within their respective political boundaries, in effect creating the Northern Ireland and Republic of Ireland teams we know today. Though Northern Ireland continued to play as ‘Ireland’ in British Home Championships until the 1970s, partition had by then become a permanent fixture in Irish football.