Two Great Communal Leaders: James Craig (1871–1940) and Joe Devlin (1871–1934)

04 March 2021

.png)

Professor Lord Bew, Emeritus Professor of Politics, Queen’s University Belfast.

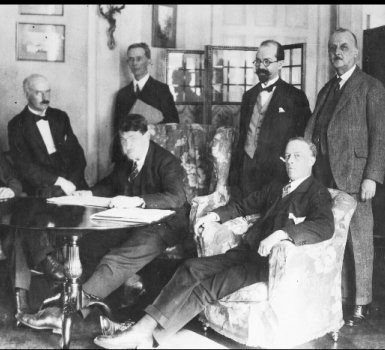

One hundred years ago, the political leadership of the two communities in Northern Ireland effectively lay in the hands of two men, James Craig and Joe Devlin. They were very different: Craig was born into a wealthy family, Devlin came from a poor working class background. Both made tactical mistakes but neither man was petty. Both men made substantial reputations for themselves in Westminster.

James Craig

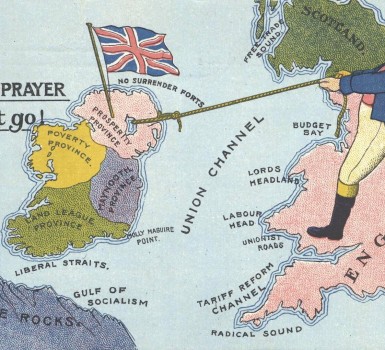

Craig’s early years in politics were dominated by the strength of the land reform politics of T.W. Russell, which presented a serious challenge to the political ambitions of the Craig family. This formative experience left him throughout his career with a perhaps exaggerated fear of the willingness of Protestants to split on social issues and thereby weaken the Unionist cause. In 1922, the senior British civil servant S.G. Tallents described Craig as having ‘a great desire to do the right and important thing: not a clever man but one of sound judgement and can realise a big issue'. But he also noted critically that ministers were ‘too close to their followers’ – a serious problem throughout the first five decades of devolution.

Alas, both Craig and Devlin at times employed the language of threat – Craig was more culpable here than Devlin. But on the positive side, Craig always set his face against an explosive all-out sectarian civil war. He played a major role in the ‘peace process’ of 1921–22, by meeting Eamon de Valera before the truce in May 1921, a physically brave act at a time of serious violence. In doing so Craig put himself in the service of the doves of the peace-making faction of the British State, a faction much distrusted by other Unionists. Again in 1922, Craig twice negotiated pacts with Michael Collins. He faced down senior Unionist critics who hated this search for compromise with republican men of violence. In 1926 he was capable of saying:

The North and South have got to live together as friendly neighbours: So it is for the government of the South and the government of the North to turn their hands rather from the matters which may have divided them in the past to concentrate on the matters which really affect the welfare of the people in their own area with a view that the whole of Ireland, and not one part of it alone, may be prosperous.

But in 1927, he announced the abolition of proportional representation which understandably infuriated Joe Devlin.

Joe Devlin

The Nationalist politician Joe Devlin (1871–1934) is a figure of enormous complexity. When Parnell came to Belfast to give his conciliatory speech in May 1891, Devlin, a youthful anti-Parnellite in the split, attacked his carriage. In the early 1900s Devlin was an opponent of the local Catholic bishop. In 1902 he became the MP for Kilkenny. He was the loyal and principal ally of John Dillon, alongside John Redmond, the key leader of the Irish parliamentary party in this era. Devlin became the leading figure in the powerful Ancient Order of Hibernians who helped many access the New Liberal welfare reforms after 1906. Joe Devlin became the hero of Belfast’s Catholic factory workers, especially the female linen workers. Henry Patterson’s important recent essay on Bangor shows how much Devlin contributed to improvements in their lives. On the other hand, critics like the Cork MP William O’Brien pointed out that it was a sectarian Catholic-only organisation – mirroring the Orange Order on the other side – which neither Parnell nor Tone could have joined.

Devlin initially resisted any form of partition in the Home Rule crisis but in the end came to accept John Dillon’s view of 1914 that it was wrong to coerce the Unionists. He was never, however, a supporter of the Belfast parliament and his involvement after 1926 was either ‘languid’, in the Northern Whig’s phrase, or sharply critical of the government.

Interestingly, he criticised the Unionists not just for their sectarianism but also their social conservatism. In a speech in early 1921, he asked ‘what bond of comradeship could he feel with men who in the past voted against such reforms as Old Age Pensions[?]’ He had applauded Winston Churchill’s vision of Home Rule as expressed in Churchill’s Belfast speech of February 1912, in which Churchill promised that after Home Rule Irish old-age pensioners who drew a state pension ‘as their last refuge on this side of the grave,’ would continue to receive it. The irony here, of course, is that an independent Irish government in 1924 had to cut the level of pension support inherited from the UK, while the Unionists in the north were able to sustain it. Devlin was not surprised. He was a lifelong opponent of Sinn Féin precisely because of his concerns on such a point.

Legacies and Commemoration

Devlin’s attractive and warm personality transcended politics. There was genuine Unionist grief at the moment of his death. Sir Edward Herdman insisted that Devlin commanded large-scale Unionist respect, while John Johnstone delivered what was styled as the ‘Omagh Unionist tribute’: they might not agree with his politics, but ‘the country had sustained the loss of a generous charitable gentleman, who, according to his views, fought wholeheartedly in the best interests of his native land.’ The most interesting account came from the veteran Northern Whig writer, ET Robinson:

“Our Joe” as old Northern Nationalists used affectionately to call him said many bitter things in the course of political word warfare but he never did a mean or unkind action … Apart from politics, everybody who knew him liked Mr Devlin, and his quick sympathy with distress or trouble of any kind made him regarded with real affection by a large portion of the community.

Joe Devlin was decidedly not a republican, but was never impressed by the parliament of Northern Ireland even after his decision to drop abstention in 1926. But the fact remains that he was always an important presence in Belfast as he was in Westminster. James Craig’s importance is acknowledged in a physical sense in the Stormont central hall. Lord Carson, although he never sat in Stormont, was acknowledged in a statue even though he, like Devlin, was unenthusiastic about devolution in Northern Ireland.

Is it not time to mark also the role of Joe Devlin by some physical monument? At this centenary moment, it is time to challenge the fact that he was the one truly great actor of 1921 who is not properly acknowledged in the building of our parliament.