The Political Partition of Ireland Was Not Followed by a Social and Cultural One

14 June 2021

Dr Cormac Moore, historian-in-residence with Dublin City Council and author of Birth of the Border: The Impact of Partition in Ireland (Merrion Press, 2019).

To understand more comprehensively the consequence of the division of Ireland 100 years ago, it is important to assess the partition of Ireland through an integrative (top-down and bottom-up) approach on how matters of state policy impacted on the everyday lives of people and organisations they were involved in.

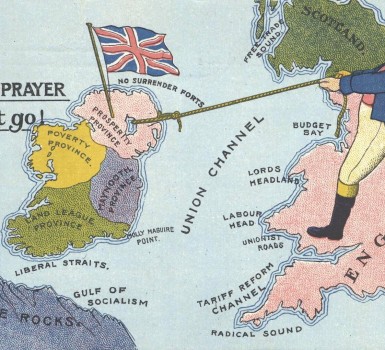

The Road to Partition

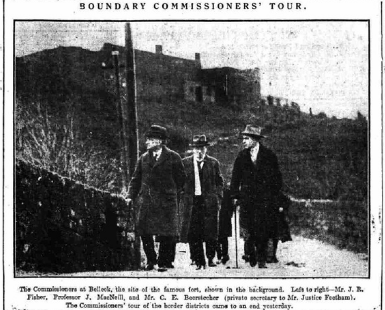

The path to partition was long, uncertain and meandering. The narrative of partition being an inevitable and pre-determined ‘solution’ between Ulster Unionists and Irish Nationalists is too simplistic. The decade from 1912 saw many twists and turns that brought about partition. Certainty realistically only arrived in 1925 with the decision to retain the status quo after the Boundary Commission debacle. The process of partitioning Ireland being dragged out for years resulted in great confusion and ambiguity.

For many the creation of the border was merely an administrative inconvenience until tangible form was given to partition with the introduction of customs barriers in 1923. Then, the border became real and entered the everyday for those on either side of it. With all borderlands being fluid and dynamic human constructions, including long-established borders such as the Pyrenean border between France and Spain, they are all alive and contested. Given the piecemeal and lengthy implementation of partition in Ireland, people and organisations responded to it in many different ways.

Two Irelands?

The political partition of Ireland was not matched by a social and cultural one on the island, by and large. The two Irish political jurisdictions that came into existence after partition allowed social and cultural organisations to react to the creation of the Irish border as they saw fit.

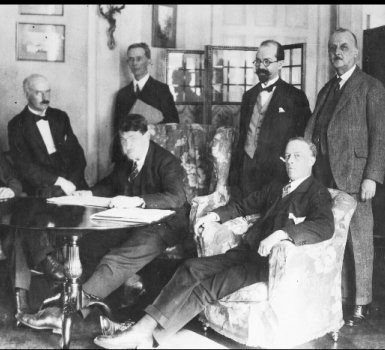

Politically and economically, both Irelands moved further and further apart. Politically, Ulster Unionists looked to cement partition, while the Irish Free State’s public rhetoric opposing partition was not matched by its actions of doing nothing to prevent it. However, many organisations with a strong unionist and Protestant make-up, including the three main Protestant denominations (Church of Ireland, Presbyterian, Methodist) have all remained all-Ireland bodies since partition.

Although required to be mindful of the new political realities on the island, most organisations were neither compelled to nor desired to split along political lines. Some bodies were comprised of members who held the anomalous position of supporting political partition on the one hand and embracing unity on an all-Ireland basis through their organisation on the other. For example, John Miller Andrews, the Minister for Labour in James Craig’s first Northern government and his successor as Prime Minister in 1940, while seeking as much divergence politically between the North and the South, actively supported unity in hockey on the island.

The ambiguity, fluidity, and uncertainty surrounding partition provoked many responses from organisations in religion, trade, labour and sport, the most common one being to remain governed on an all-Ireland basis in post-partition Ireland. Sports, such as rugby and golf, that remained governed on an all-Ireland basis, adapted to partition by incorporating inoffensive and neutral flags, anthems and emblems, tailored to accommodate diverse political and cultural interests. Dublin and Belfast continued to share hosting Irish international rugby matches, albeit with hiatuses during the 1920s and 1950s. Trade unions, such as the Irish Trade Union Congress (ITUC), democratised internal governance structures to limit the scope for divisions and were mindful of the geographic dimensions within their organisations. For many bodies, a federalist approach to internal governance was the clearest path to internal unity.

A Zone of Interaction

For those organisations that remained united, by discarding partition within their own structures, it showed that people and organisations on the ground were not beholden to decisions emanating from the political centre. The border became a zone of interaction as much as it was one of division. There was no compunction nor obligation for most organisations to follow suit once the new international frontier was created with the partition of Ireland.

This is, in many respects, a unique feature of the partition of Ireland compared to other divided societies. Even with the separation of the law between both jurisdictions under the Government of Ireland Act 1920, unity existed up until 1926 in the bar where all Irish barristers, North or South, had the right of audience in both areas of Ireland preserved to them and everyone on the island had to qualify as a barrister through King’s Inns in Dublin.

According to historian John Whyte, Irish organisations remained all-Ireland entities for a variety of reasons, such as historical inertia, financial reasons, self-interest, and pragmatism. They were allowed to pursue their ‘local interests’ without becoming subsumed by ‘the iron grip of the nation-state’. The labour leader William O’Brien was in many ways correct in 1926 when he claimed ‘Partition … prevails almost exclusively in the political sphere’. Even in the political sphere, Unionist politicians agreed to maintain all-Ireland functions for lighthouses and postal services for pragmatic reasons.

For bodies with a homogenous profile, there was little difficulty in remaining united. For those like soccer and the labour movement, partition highlighted the differences among their membership. Numerous organisations had complex identity profiles that do not fit into the simplistic binary one purely between Irish Catholic Nationalists and Ulster Protestant Unionists. Many with a diverse demographic still remained united by acknowledging the changed circumstances and by introducing new structures to accommodate members based in Northern Ireland.

Pre-partition practices continued with most organisations after the onset of partition. Organisations founded before 1921 tended to continue on their previous all-Ireland basis, while organisations founded after 1921 were more likely to observe the border. It was rare for any organisation to split on a North-South basis that was formed before 1921. The partition of bodies in Ireland was only common to those with direct links to the Northern government; including government departments; statutory bodies for professions like the pharmaceutical industry; and lobbying groups.

It is clear, whether for Ireland or any other borderland, that states do not simply impose their values and boundaries on local society. In many instances, with pragmatism trumping politics, people and organisations are more interested in pursuing local interests rather than following particular political or identity ideologies.