The Belfast Shipyard Expulsions

29 March 2021

Professor Henry Patterson, Emeritus Professor of Politics, University of Ulster.

By the spring of 1920, the War of Independence was beginning to impinge on the province of Ulster. There were growing fears among Unionists that IRA violence was extending northwards. Sinn Féin’s success in the local government elections in January, particularly in Derry where nationalists had gained control of the city for the first time, contributed to the unease. During the Easter weekend the IRA launched arson and gun attacks on police barracks, tax offices and other government buildings, and in May the head of the Special Branch in Derry was the first RIC man to be killed in the north-east of Ireland. In June intercommunal violence in the city left twenty dead.

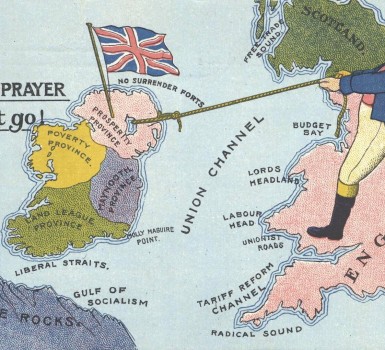

Apart from concerns about the IRA campaign, there was also a widespread loyalist belief that the war years had seen the ‘peaceful penetration’ of Ulster by Catholics from the south, who had taken the jobs left by Protestants who had enlisted. This theme was promoted by the Ulster Unionist Labour Association (UULA), an organisation formed in 1918 by the Ulster Unionist Council. It drew heavily on militant loyalists who worked in the Belfast shipyards. Its president was Sir Edward Carson who, like many other British and Irish conservatives, was afraid that the example of the Bolshevik revolution was encouraging a wave of militant trade unionism and socialist agitation, which was in alliance with Sinn Féin and anti-colonial nationalist movements to destroy the British Empire.

‘A Match to the Gunpowder’

Unionist political leaders were concerned about the influence of trade union militants and socialists on normally loyal Protestant workers. In January 1919 engineering workers in Belfast had gone on strike for a reduction of their working week from 54 to 44 hours. The strike shut down much of the city’s industry for three weeks and was only ended when troops were brought in. In municipal elections in January 1920 Labour had won 20 percent of the poll. UULA councillors, Unionist politicians and newspaper editors hammered out a message of collusion between Labour and Sinn Féin. In the words of a UULA candidate in the Shankill area:

The insidiousness of their opponents was that they were afraid to come out into the open but were trying to creep in under the cloak of labour. If they returned socialists these people would be found passing resolutions in favour of Home Rule.

At the 1920 annual 12th July demonstration in Belfast Sir Edward Carson had warned the British government that, if it did not support the loyalists of Ulster by enrolling them in a special constabulary to combat the IRA, they would take their security into their own hands. Into this febrile atmosphere came the news of the high-profile IRA assassination in Cork of the Divisional Commissioner of the RIC, Lieutenant Colonel Gerald Bryce Smyth. Smyth was a native of Banbridge and the killing caused intense anger amongst loyalists. The burial in Banbridge on 21st July coincided with the return to work in the shipyards after the July holidays. According to the Belfast Police Commissioner, the resumption of work so soon after the murder in Cork acted ‘as a match to the gunpowder’.

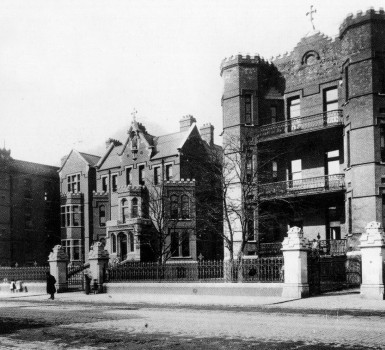

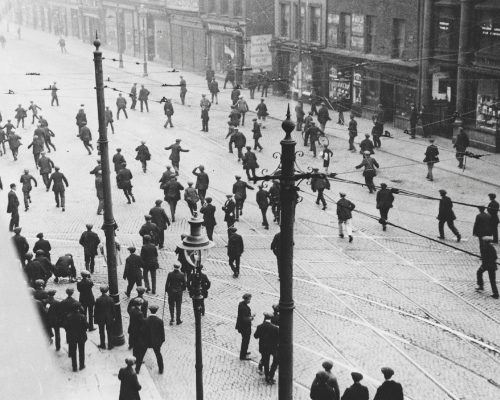

At this time Belfast’s two shipyards, Harland and Wolff and the smaller Workman Clark yard, employed 36,000, an all-time high. A lunchtime meeting of shipyard workers on the 21st July was organised by the Belfast Protestant Association outside the gates of Workman Clark’s south yard. Hundreds attended, as did a group of unemployed ex-servicemen. They listened to denunciations of IRA attacks and complaints about Belfast industrialists employing ‘disloyalists’.

Afterwards a mob marched through the premises of Harland and Wolff ordering all Catholics and hundreds of Protestant socialists and trade unionists to leave. Some were beaten, kicked and pelted with rivets and stones. In all about 2,200 workers were expelled from the yards. Expulsions spread to other engineering works, and also into linen mills and factories. Overall approximately 7,500 workers lost their jobs, including 2,000 women. Over 1,800 Protestants were expelled, including ex-servicemen and members of the Orange Order.

Aftermath

Harland and Wolff and other employers now found that they had lost essential workers and that production was being harmed. However, their attempts to get some of the expelled workers back met with resistance from ‘vigilance committees’ set up by UULA militants, who demanded that any returning worker signed a declaration of loyalty to George V and a repudiation of Sinn Féin.

In September 1920, Sir Ernest Clark was appointed Assistant Under Secretary for Ireland and sent to Belfast to help with the establishment of the new administration. Sir Hamar Greenwood, the Chief Secretary for Ireland, instructed Clark that ‘it was a matter of paramount importance’ that expelled workers had their employment restored. Clark had some success in getting the vigilance committees to drop the loyalty declarations and some expelled workers had begun to return. However, the IRA assassination of two RIC constables sparked more sectarian violence and the possibility of any widespread return vanished.

For many nationalists the expulsions were the product of a state-inspired pogrom. However, the term pogrom usually signifies violence directed against one religious or ethnic group. Catholics did bear the brunt of violence and intimidation, but it was also aimed at the labour and socialist traditions which enjoyed the support of a substantial minority of Protestants. Unionist politicians did not instigate the expulsions, but their campaign against an alleged Labour/Sinn Féin alliance helped to legitimate the intimidation and thuggery of groups like the Belfast Protestant Association. In October 1920 at a ceremony to unveil a giant Union Jack in the valve and brass fitting department in Harland and Wolff, Sir James Craig addressed the workers: ‘Do I approve of the action you boys have taken in the past? I say “Yes”’. As the post-war economic boom ended and unemployment rose, the prospects for the expelled workers darkened.

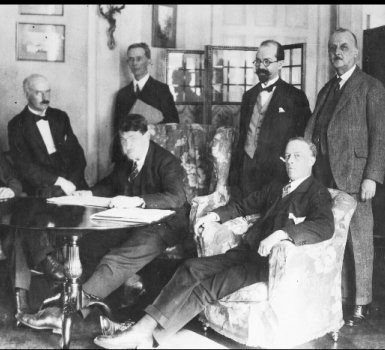

In March 1922, Craig and Michael Collins signed a pact in which Craig agreed to try to get the expelled workers reinstated, while Collins would call off the boycott of Belfast goods. But a British civil servant, sent to report on conditions in Northern Ireland, noted two main obstacles. One was the high level of unemployment at the time. The other was that ‘Ministers are too close to their community and cannot treat their ministries as from a distance’. Many of the expelled workers never got their jobs back. The shipyard expulsions would cast a long shadow over the subsequent history of Northern Ireland.