From Partition to Decriminalisation: Homosexuality in Northern Ireland 1921-1982

22 September 2021

On 11th February 2020, nearly a century after the partition of Ireland, the first same-sex marriage in Northern Ireland took place between Robyn Peoples and Sharni Edwards-Peoples. The Belfast ceremony followed the enactment of the Northern Ireland (Executive Formation etc) Act 2019, a measure occasioned by a suspended Northern Ireland Executive, Westminster intercession, and inspired by human rights concerns.

This uniformity of standards across the United Kingdom was overdue, marking some six years since equal marriage had been legitimized in England, Wales, and Scotland. Marriage equality in Northern Ireland likewise lagged behind the equivalent ruling south of the Irish border, which had been provided for by public referendum in 2015.

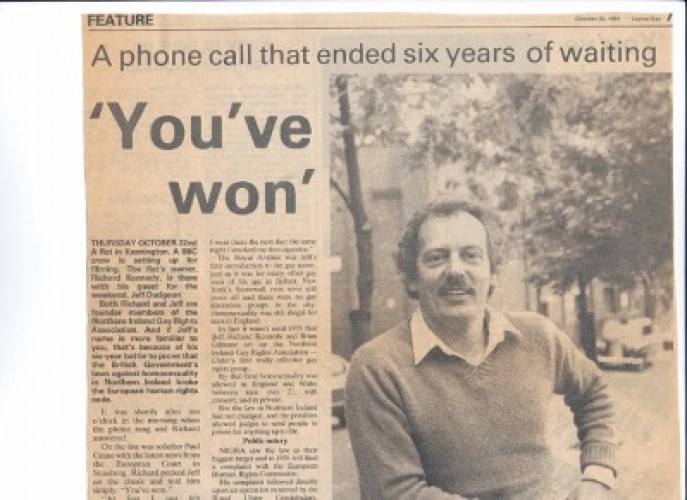

This was not the first time that ‘external’ governance would force Northern Ireland to shift its stance on LGBTQ+ rights. In 1982, fifteen years after the Sexual Offences Act 1967, the partial decriminalisation of male homosexuality was extended to Northern Ireland after a Belfast shipping clerk, Jeff Dudgeon, successfully petitioned the European Court of Human Rights. Dudgeon’s 1981 case was the first at Strasbourg to be decided in favour of LGBTQ+ rights and set a precedent that would later be replicated by Senator David Norris for the Republic of Ireland in 1988.

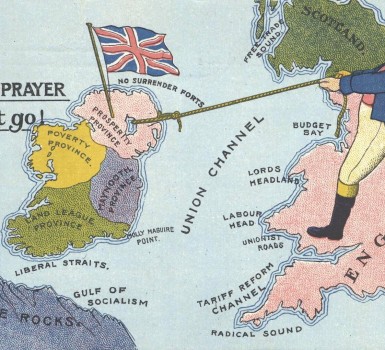

Both legal milestones had profound implications regarding the constitutional status of Northern Ireland, and the autonomy of devolved government at Stormont. When it came to the regulation of sexual behaviour, Northern Ireland was a ‘place apart’ from other regions in the UK, and more in line with the Catholic conservatism of the independent Irish state. Northern Ireland’s sectarian conservatism and assigned Parliament at Stormont meant that laws relating to sexuality were applied differently than in the rest of the United Kingdom, further evidencing the region’s long desired half-in-half-out status within the Union.

In 1921, both new Irish parliaments inherited Victorian legislation including the 1861 Offences Against the Person Act and the 1885 Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, which upheld the illegality of all male homosexual acts. The latter famously resulted in the imprisonment of Oscar Wilde in 1895 - and his prosecution by the well-known lawyer and Unionist ‘hero’, Edward Carson - , but many Ulstermen were also prosecuted under these restrictions. Encounters took place in picture houses, alleyways, workhouses, public lavatories, and private bedrooms.

For example, in November 1966 two young men in Larne talked about the weather and sat down together. One remarked “What would you say if I told you I was a fruit?” and the other replied “It’s all the same to me”, after which they had sex. In a statement after being charged with buggery, one of the men pronounced “This is not a normal habit of mine. It was the only time it happened. I think it was because I had drink taken”, a justification that is customary across the court records of this time period.

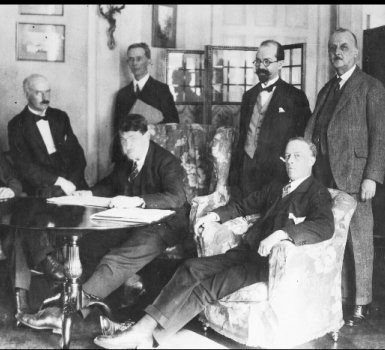

In 1954, amidst a series of convictions which raised British public consciousness about the prevalence of homosexuality, a Westminster committee headed by John Wolfenden was appointed to consider and recommend changes to relevant laws and to appraise the treatment of those convicted. The Committee comprised fifteen members and received testimonials and written statements from hundreds of witnesses, though Ulster was significantly underrepresented throughout these proceedings, in terms of witnesses and committee membership. The final report of the Wolfenden Committee was published in 1957 and recommended the partial decriminalisation of private, consensual sex between males over 21 years old. Female homosexuality was never formally outlawed in the same way. It would take another decade for this recommendation to become law, and the resulting Sexual Offences Act 1967 was not extended to Northern Ireland, nor to Scotland, until the 1980s. Scottish exclusion was motivated by objectors on the Wolfenden Committee like James Adair and can also be explained by Scotland’s separate legal system, where prosecutions for homosexual offences were subject to a much higher standard of proof. In Northern Ireland, as was the case for the Abortion Act of the same year, decriminalisation was not extended as this was deemed the responsibility of Stormont.

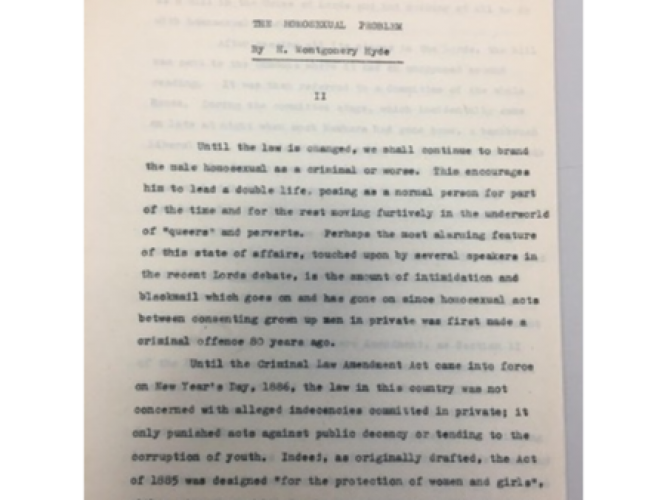

Nevertheless, H. Montgomery Hyde, the Ulster Unionist MP for Belfast North from 1950-1959, was a vocal proponent in favour of the decriminalisation of homosexuality. At the Westminster House of Commons on 26th November 1958, Hyde delivered a half-hour speech during which he fervently argued, ‘the great majority of homosexuals merely indulge in an affectionate relationship, conduct which was not criminal in this country before 1885 and which is not criminal in most Continental countries today’. Such advocacy ultimately resulted in his de-selection in 1959, ‘as a result of criticism amongst constituents over his attitude over certain problems particularly the Wolfenden Report.’

It wasn’t until the following decade that momentum for homosexual law reform in Northern Ireland would be renewed. LGBTQ+ activism in Northern Ireland stemmed from the Gay Liberation Society at Queen’s University Belfast, established in 1971. The early 1970s also saw the foundation of Cara-Friend, a ‘voluntary befriending and information organisation for homosexual and bisexual men and women.’. This offered social support and integration, as well as targeted services for transvestites, transsexuals, and lesbians.

The Northern Ireland Gay Rights Association (NIGRA) was the driving force behind the decriminalisation of homosexuality in the early 1980s. Its broad objective was political, with a wider ambition of abolishing ‘all the laws currently governing sexual activity’. This movement for gay rights was an all-Ireland phenomenon, with friendship, comradery and counsel developing between organisations north and south of the border.

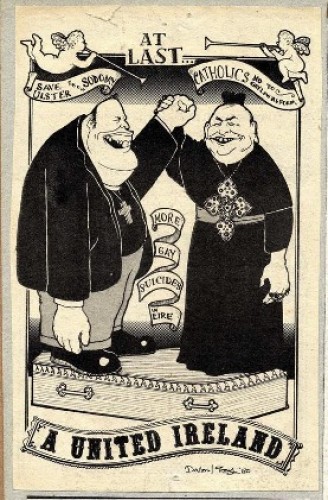

These groups operated amidst a context of ethno-nationalist conflict and fundamentalist religion, both of which were peculiar to Northern Ireland. Polarised Catholic and Protestant devotional cultures found rare common ground in their moral intransigence and were often at the forefront of anti-gay rancour. Rev Ian Paisley and the Democratic Unionist Party headed a “Save Ulster from Sodomy” campaign in the 1970s, co-ordinating a petition that attracted 70,000 signatures in their resistance of homosexual law reform.

Though such resistance delayed proposed reforms from Westminster, Europe’s status as a guarantor of LGBTQ+ rights was effectively deployed to yield change. Dudgeon’s case at Strasbourg circumvented both local and national legislative bodies, during a time when Direct Rule was in place. The European Court of Human Rights ruled that Northern Ireland’s anti-homosexuality laws, and the police investigations these occasioned, were in violation of Article 8 of the European Convention of Human Rights. This would be replicated for the Republic of Ireland by Senator David Norris in 1988, following a failed 1983 case at the Irish Supreme Court where the ‘Christian and democratic nature of the Irish state’ was invoked against decriminalisation.

One hundred years after partition, much has changed for the LGBTQ+ community in Northern Ireland. Though notably more visible and more assertive, LGBTQ+ rights have continued to come after the rest of the UK and Ireland. The constitutional status of Northern Ireland, as established under the Government of Ireland Act 1920, has thus simultaneously functioned to exclude the region from the extension of measures that protect the rights and status of its LGBTQ+ population, whilst Northern Ireland’s position at the intersection of British, Irish, and European influences has ensured the equalisation of these standards, however belatedly.

Abigail Fletcher, PhD Researcher, University of Edinburgh