Focus on … Minorities, Partition and the Formation of Northern Ireland

04 May 2021

In this instalment of our Focus On series, Nadia Dobrianska explores contemporary views of different minority communities on the island of Ireland, and how they were affected by partition and the formation of Northern Ireland in 1921.

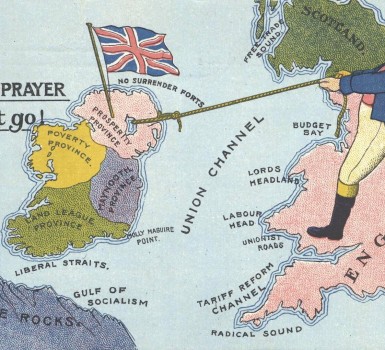

The partition of Ireland resulted in the creation of two new states with solid majorities: a Protestant majority in Northern Ireland, and a Catholic majority in what became the Irish Free State. The decision to partition Ireland appeared to the British government to be the best solution, satisfying both the demand of Irish nationalism for Home Rule, and Ulster Unionism’s opposition to becoming a minority in a predominantly Catholic Ireland.

However, partition left behind sizeable minorities of Catholics in the North and Protestants in the South. The Catholic minority accounted for approximately one third of the population of Northern Ireland, while Protestants made up 7% of the population of ‘Southern’ Ireland. In this respect Ireland was going through a similar process to much of Europe after the First World War.

Although Catholics in the North and Protestants in the South differed in many ways, they faced similar challenges of how to deal with partition and the formation of Northern Ireland. During the revolutionary period many faced violence and intimidation. Catholics were severely afflicted during the so-called ‘Belfast troubles’. Protestants in border counties and in the South faced boycotts, intimidation and violence. Significantly, both minorities were opposed to the Government of Ireland Act of 1920 and the partition of Ireland.

The two minorities came to terms with partition in different ways. Some Protestants in the South chose to leave Ireland, many resettling in Britain; others accepted the new government and stayed. However, as Southern Unionists became politically marginalised, many Protestants in the border counties resettled in Northern Ireland. Similarly, many Northern Catholics sought refuge in the South from the Belfast troubles in 1922, but were forced to return due to the outbreak of the Civil War. Hopes that the Boundary Commission, which met in 1924, would recommend significant transfers of the territories to the Irish Free State were not fulfilled, thus leaving Northern Catholics an alienated minority within Northern Ireland.

Below you can find a selection of reports about and declarations from minority communities on the island of Ireland, giving a snapshot of how they viewed their respective positions.

Speech by TP O’Connor MP to House of Commons, 29 March 1920, on the Government of Ireland Bill

This is a moment so grave and so tragic in the history of Ireland, in the history of England, and in the history of the world, that I deem it my duty to keep a curb on every strong feeling I have as regards the proposals of the Government and to discuss them in what I hope will be a perfectly calm and candid spirit. … I have no hope that any words I may utter today by way of warning will receive any greater attention from the Government than those which they have neglected in the past.

… It is said that the rights of minorities will be protected. That question will be stated much better than I can by the Southern Unionists; but what becomes of … the future of Protestantism and of the Protestants in Ireland? A favourite cry when this struggle began, many years ago, was that Home Rule was Roman, and that all the Protestants, therefore, would be deprived of all their personal and religious liberty. In face of that cry, the big Protestant brother of the North abandons his weaker brother to the mercy of all those bigots and persecutors who mean to interfere with his religious and personal liberty.

… What about the Covenanters of Donegal and Cavan and Monaghan? I understand that if any particular item in the Covenant is more vehement or more resolute than another, it is that, under no circumstances or conditions whatsoever, should that Protestant minority of Donegal and Cavan and Monaghan be abandoned by their co-religionists in the six counties; yet the Covenanters of Donegal and Cavan and Monaghan are given up to the Papists and Nationalists.

It may be a surprise, to some English hon. Members at least, to hear that there is a considerable Catholic and Nationalist minority in the six counties. … That minority is left entirely at the mercy of the Northern part. … This Bill, which rests upon the protection of the rights of minorities, is full of proposals to abandon all the minorities of Ireland.

Speech by Joe Devlin MP to House of Commons on the Government of Ireland Bill, 30 March 1920

What is the character of the partition? Let us look at that. In the first place, there is to be a Parliament for 26 counties. Under that Parliament there will be nearly 3,000,000 Catholics and 250,000 or 300,000 Protestants, but there will not be, unless by generous goodwill, a single Protestant or Unionist elected for that Parliament. The great body of the Southern Unionists will not have a single representative in it. But in Ulster, in the six counties, where the Catholics are 380,000 or 480,000 out of a population of 850,000, there will be representation which will constitute them a permanent minority in that Parliament. I cannot understand why this partition Bill was introduced at all.

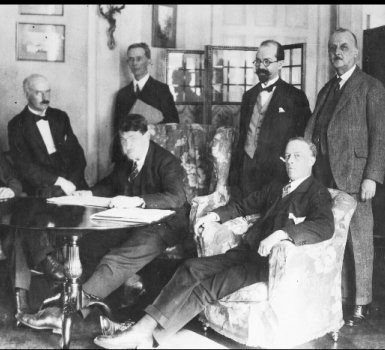

Statement of the Executive Committee of the Irish Unionist Alliance, 17 February 1921

The Executive Committee of the Irish Unionist Alliance have considered the situation arising out of the passing of the Home Rule Act, 1920, and, having consulted with the representatives on the General Council of the Alliance of the county branches in Southern Ireland, and the other members of the General Council, so far as existing circumstances permitted, are satisfied that the overwhelming body of opinion of Southern Unionists whom they represent supports the conclusions at which they have arrived.

At a time such as this the Imperial Parliament has decided to attempt an experiment in Home Rule. What should be the attitude of Southern Unionists? In Northern Ireland, in order to avoid being placed under a Separatist Parliament in Dublin, they have undertaken to try and work their own Parliament with the object of achieving a closer union. They can afford to try, for the constitutional elements predominate there. Unionists in Southern Ireland are confronted by different conditions.

A Parliament is essentially a peaceful institution, and so long as the atmosphere in Southern Ireland continues that of a civil war, this Committee considers that it is impossible that Southern Ireland can achieve any satisfactory form of self-government subordinate to the Imperial Parliament can ever be established.’

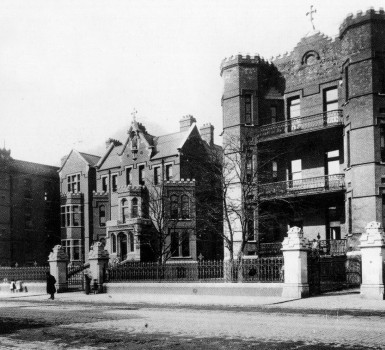

Resolution Adopted by Nationalist Conference at St Mary’s Hall, Belfast, 4 April 1921

‘That this convention of representative Nationalists from the six counties in Ulster, hereby places on record its unalterable belief in the right of Ireland to determine its own destinies according to the aspirations of its own people; that we regard the establishment of a Parliament for a section of this Province of Ulster as a menace to public unity and a danger to the lives and interests of our Northern citizenship, and we feel it our duty to declare alone in a constitutional assembly for all Ireland lies the hope of well-ordered freedom and a spirit of brotherhood and goodwill amongst Irishmen of all creeds and classes. […]

That believing that this so-called Northern Parliament is a danger to our liberties and a barrier to the permanent solution to Irish problem, we can give it neither recognition nor lend it support, and we call on all those who are opposed to the partition of Ireland to support at the forthcoming North-East Ulster Parliament only candidates who will unreservedly pledge themselves neither to recognize nor enter into it, and for this purpose we authorize the calling immediately of conference to select candidates pledged on the policy of self-determination and anti-partition.’

‘Treacherous and Vile’: Nationalist Take on Differing Treatment of Protestants in the South and Catholics in the North

(The Freeman’s Journal, 13 June 1921)

The endeavour of the politicians and Partitionists of the Northern Church organisations to convert the political struggle in the South into a religious war is reckless, treacherous, and vile.

Three hundred thousand of their Protestant co-religionists are scattered through the South, dependent upon their Catholic neighbours in hundreds of thousands of cases for the means of business and industry, and the charities of life.

They have been abandoned by the Partitionists after they had sworn that the Northern Covenanters would never desert their Southern fellows. But base as that act of treachery was, it was not so base as the attempt now to light the fires of religious hatred and persecution round them, for the purpose of Partitionist and British propaganda.

No Protestant has suffered in the South for his religious beliefs. When the Belfast pogroms took place last year hundreds of Southern Protestants stood forth to protest and to proclaim their good relations with their Catholic neighbours.

The Presbyterian General Assembly was opened by an address from the outgoing Moderator, in which he said:

‘Wherever I have gone in the South and West I have heard our people state that, amidst a fearful political upheaval and unpardonable atrocities which have been committed in their midst, as yet there is not one trace of religious war manifesting itself’.

Similar testimony was forthcoming from every Southern member of the Assembly who took part in its discussion.

But the politicians who prostitute the Assembly, and who are ready to pervert the institution that they profess to regard as ‘the Bride of Christ’ into a political strumpet, would have none of this testimony. Against it they set out the following ‘report’:

‘Language fails to describe the conditions under which many of our people are living in disaffected areas. Quiet and law-abiding people are being put to death in the most inhuman and cold-blooded manner, and in some districts the Protestant population is being entirely exterminated’.

The gentleman who presented this report is the Chancellor of the Exchequer in the new ‘Parliament of Northern Ireland’.

His sponsorship of the vile libel is an earnest of the spirit in which the Northern Government will get to work.

A practical application of the spirit is forthcoming. On Friday at the Assembly some of the members protested because special provision had not been made for the special representation on the Southern Senate of the forty-nine thousand Presbyterians, who are all that are to be found in the twenty-six counties.

On Saturday the Northern House of Commons exercised its privilege of choosing for itself its own superintending Senate. Among the twenty-four Senators chosen not one Catholic is to be found, though Catholics are nearly forty per cent, of the Six Counties.

What hypocrites these people are to be sure! Fortunately, their hypocrisy is so repellent that there is no danger of its imitation.

Letter from Southern Unionist Major Somerset Saunderson, commenting on partition, December 1921

‘Now I have no country.’

Elections to the Northern Ireland Parliament After Abolition of Proportional Representation

(Irish Independent, 20 March 1929)

‘The Parliamentary Elections for Northern Parliament, it is believed, take place probably about May 14 or May 15. [...] Mr. Joseph Devlin, who at present represents West Belfast Nationalists and who at the next elections will stand for the Central Division, will probably contest West Belfast for a seat in the Imperial Parliament. [...]

At the last general election in 1925 Republicans and Nationalists in the Six counties returned only twelve candidates, although on a popular basis they were entitled to seventeen. Under the new gerrymandering system they cannot hope even for twelve.

With the possible exception of Fermanagh, Co. Antrim under the new system is likely to fare the worst. Under P.R. [Proportional Representation] it had seven representatives and returned one Nationalist, Mr. T.S. McAllister, who came third on the list defeating two Government Parliamentary Secretaries. Under the new system the county can have no Nationalist representative, although there is an overwhelmingly large Nationalist population in one area of the county. This area has now been sliced in such a manner that every chance has virtually vanished. [...]

As Nationalists number over 38,000 of the 190,000 of the entire population, there is a feeling of bitter resentment against the system that precludes any possibility of their being adequately represented.’