Ernest Clark, ‘Midwife’ of the Northern Ireland State

15 September 2021

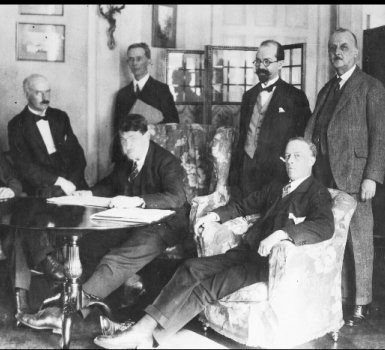

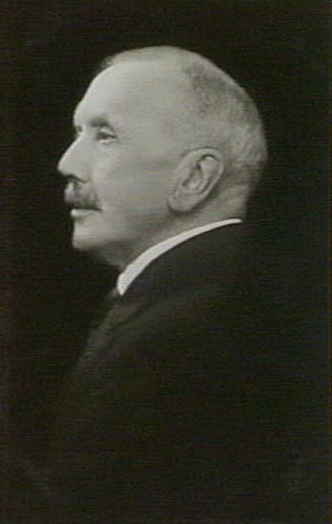

Ernest Clark is comparatively unknown, yet no one did more to transform ‘Northern Ireland’ from its nominal existence on a parliamentary bill into reality. Basil Brooke described him as the ‘midwife… of Ulster.’ He was a highly capable Englishman who believed that working ‘to exhaustion’, sixteen hours daily, was ‘not an evil but a benefit to the vigorous constitution.’ He had entered the civil service in 1881, the inland revenue legal branch, and combining this with academic studies, was called to the bar in 1894. By the 1900s he had become a leading tax expert whose advice on tax procedures was sought by foreign governments. By 1919 he was Chief Inspector of Taxes and, in 1920, was knighted.

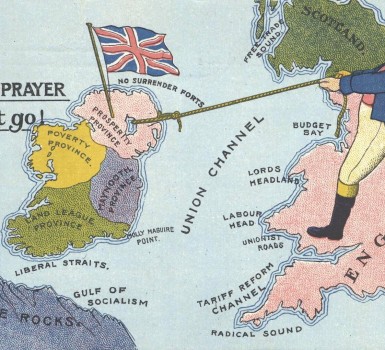

His departmental superior, Sir John Anderson, was appointed Irish Undersecretary in May 1920, and it was he who appointed Clark as Assistant Undersecretary (AUS) in Belfast. Before doing so, Anderson had asked him ‘if he was… a Catholic’; Clark writes: ‘had I been … I could never have been accepted by the northern government.’ He also describes being ‘vetted’ by Unionist leaders, and James Craig saying to him: ‘you must write one word across your heart’, while tapping out with his finger on his chest: ‘ULSTER.’ It was Craig who had requested that a civil servant be appointed to prepare for partition.

Clark arrived in Belfast on 18 September 1920. By December he had recruited twenty staff to his Belfast city centre office, protected by an armed police guard and steel screens fitted internally. Dublin Castle dictated his first priority – to enrol the Special Constabulary which Westminster had just agreed to form. He hoped that its establishment would reassure unionists and thus reduce the level of sectarian violence. He published details of the Special Constabulary scheme in October, and then oversaw its recruitment; 20,500 had been enrolled by late 1921. He took pride in its formation, describing its members as ‘one’s own children.’ But he was disappointed that it attracted few Catholic recruits, and was later to express concern that Craig’s government ‘could not control’ it. It was to play an indispensible role in Craig’s attempt to achieve stability and order during 1921-22.

Meanwhile, Clark had turned his attention to creating the structures of administrative partition, separating ‘Northern Ireland’ from Dublin’s governance. Unionist leaders were anxious to accelerate this process: they were aware of diminishing sympathy for their position at Westminster, and distrusted Dublin Castle because of its alleged support for an all-Ireland settlement. Their objective was to consolidate Northern Ireland’s existence so as to render it more difficult to coerce it into a thirty-two county state.

By February 1921, Clark had drafted a scheme for the future administration of Northern Ireland which, after amendment, was adopted on 25 May. There would be seven government departments, each modelled on Whitehall in organisation, procedures and practices. Meanwhile, Clark had initiated recruitment. Generally the highest grades were filled by Imperial civil servants and civil servants transferred from Dublin, while clerical and typing staff were drawn from ex-servicemen and local applicants. 800 had been appointed by December 1921. Clark had favoured reserving a proportion of posts for Catholic applicants, but he recognised that to insist on this would make his position untenable. Moreover, he felt growing sympathy for the Unionist leadership; he described the embryonic state as ‘trembling on the verge of the abyss.’ His strenuous efforts to have Belfast’s expelled Catholic workers returned to their workplaces had been similarly unsuccessful.

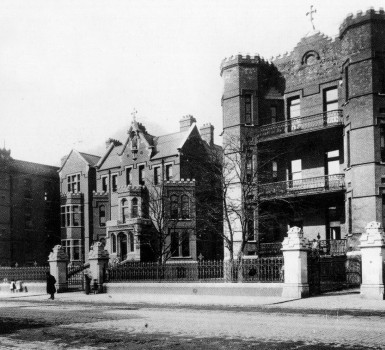

Apart from high level planning, Clark engaged in other pre-partition, preparatory initiatives – such as the acquisition of accommodation and office supplies, the transfer of files from Dublin, and a scheme for the election of the senate (its composition would mirror party representation in the Commons). He performed the groundwork necessary before polling, under proportional representation, for the lower house as well.

Clark’s diligence and energy made it possible for Northern Ireland’s first parliamentary elections to be held on 24 May, and for its government then to assume office. He had ensured that functioning, if embryonic, administrative and security structures were in place from the moment it was formed. By accelerating these events, he strengthened the Unionist position in the fluid, political circumstances appertaining at the time.

After Westminster began transferring powers to the new government in November 1921, Clark agreed to become head of its civil service and permanent secretary at the Ministry of Finance. In this capacity he conducted negotiations with Treasury officials regarding Northern Ireland’s financial relations with Westminster, and extracted concessions which were vital in securing its subsequent financial viability. After vacating his posts in Belfast in 1925, Clark held directorships in various British companies and wrote voluminously on financial issues. In 1928-29, he was a member of a British government mission to Australia to examine the continent’s economy. This proved to be a life changing experience; so favourable was the impression he made that he was invited to become governor of Tasmania in 1933. After retirement in 1945 he settled in England but, after his death in 1951, his ashes were brought to Hobart, where he was interred.

Dr Brian Barton, FRHistS